The most serious bottleneck for immigration isn’t at the border: it’s in the courts

Contenido

US immigration courts are on the verge of collapse following a silent crisis that has worsened over the years due to a significant increase in cases and a lack of judges to make immigration decisions.

While public attention is focused on the border and ICE operations, this crisis, which could be much deeper, is unfolding. According to the most recent study by the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), “Breaking the Cycle of Dysfunction at the US Immigration Courts”, immigration courts are facing the worst backlog in their history. As of August 2025, immigration courts had 3.8 million pending deportation cases, an unprecedented number that far exceeds available administrative and human capacity. This situation urgently requires both administrative and legislative reforms to transform the system.

We have learned that the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR—the Justice Department agency that houses the immigration courts) and its Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) have attempted to modernize and expedite case resolution. However, in recent years, the filing of millions of new removal cases and asylum applications from recent arrivals at the border has added further pressure to existing problems, such as an insufficient number of judges, which has overwhelmed the courts.

This increased time in resolving cases translates into longer response times for each process, meaning that thousands of foreigners take an average of four years to obtain an asylum hearing, and the final decision can take much longer if appeals are added to that.

The procedural delays and the high number of pending cases generate uncertainty for thousands of migrants and their families, having an immediate and long-term impact.

A system under pressure: structural failures and lack of resources

According to Visa Verge, the immigration court system faces structural and operational challenges that compromise its ability to respond to growing demand. First, its placement within the Department of Justice perpetuates doubts about the independence of judges, as executive branch control over the courts fuels calls to transform them into courts similar to tax or bankruptcy courts, which would operate with greater autonomy.

Adding to this debate is the excessive workload, as judges handle thousands of cases, strict deadlines, and constant pressure, factors that have led to professional burnout and mental health problems.

The historical scarcity of resources, which includes hiring specialized support staff, having adequate physical space, and even modern case management systems, also significantly limits the efficiency and quality of judicial processes.

The historical imbalance that fuels the crisis

For decades, immigration courts have suffered from serious quality and quantity problems, but these have become especially acute after the COVID-19 pandemic, due to record arrivals of asylum seekers and other migrants at the border with Mexico.

According to data from the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), in fiscal year 2024, immigration judges resolved the highest number of cases in a single year: 704,000. But DHS continued to file more cases than immigration judges could process, leading to an even greater backlog.

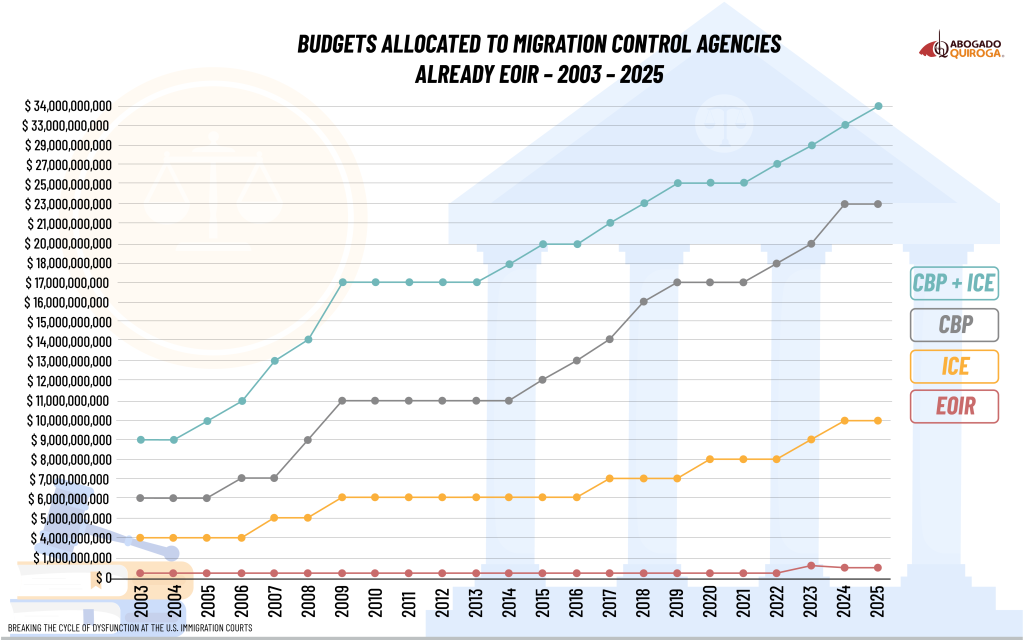

During the Biden administration, more funding for immigration courts was requested from Congress. But while the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) received slight increases, most of the budget went to funding immigration enforcement agencies like Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which have significantly larger budgets than the immigration courts.

Over the past 20 years, the EOIR budget has represented, on average, about 2% of the total CBP and ICE budgets. Just in 2024, the EOIR budget was reduced by $16 million.

From 2003 to 2025, EOIR’s budget remained virtually unchanged, growing at a minimal rate compared to immigration enforcement agencies. While ICE and CBP received increases that brought their combined budgets to over $30 billion annually, EOIR has historically remained well below these figures.

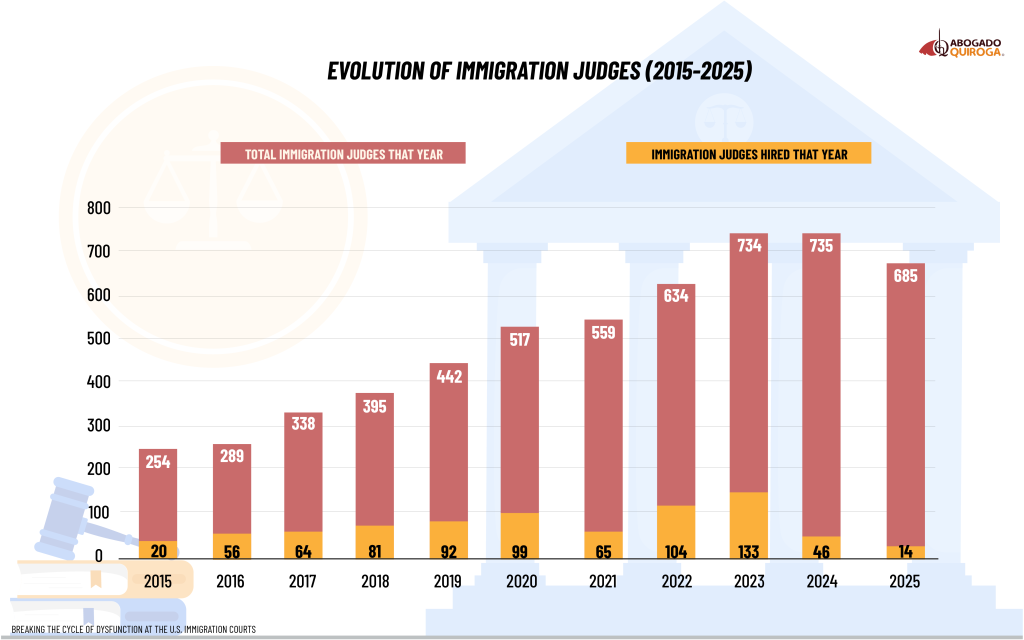

Statistics also help us understand why, instead of increasing, the number of judges for immigration courts has stagnated or decreased. The hiring of judges for these courts has not only been significantly reduced since 2023, but the 2025 levels, right in the middle of the Trump administration’s second term, are at their lowest point, comparable only to the records of 2015. This means that the current lag is abysmal, as the same number of judges are being hired as a decade ago.

This is happening while the volume of cases in immigration courts is growing exponentially, which would show that the gap between institutional capacity and operational demand is not only persistent, but structural.

What this situation indicates is that the United States government has prioritized funding the tracking, arrest, and prosecution of new cases over resolving millions of cases.

We could be talking about how this strategy has been a sustained political decision that has favored the expansion of border surveillance and control while leaving the immigration judicial system relegated and continuously underfunded.

An overwhelmed system that can’t take any more.

Over the past decade, the U.S. immigration justice system has undergone a transformation bordering on operational collapse. The number of cases backlogged in immigration courts has grown by 759 %, from 456,216 pending cases in 2015 to more than 3,8 million in 2025, according to the most recent available figures. This expansion reveals an overwhelmed judicial system, where wait times are measured in years and the workload assigned to each judge exceeds any historically recorded standard. (https://tracreports.org/phptools/immigration/backlog/)

How is the team of immigration judges in the United States funded, hired, and administered?

The funding for immigration judges in the United States comes directly from the federal budget allocated to the Department of Justice. Within this structure, the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) is the entity responsible for administering the immigration courts and managing the resources allocated for the salaries, training, and operation of immigration judges.

Each year, Congress approves specific line items within the Justice Department’s budget, which include funds to expand the number of judges, hire support staff, cover administrative costs, and maintain the technological and physical infrastructure of the courts.

This means that immigration judges do not operate independently, as is the case in the federal judiciary, but rather are independent of the executive branch. Their salaries, benefits, and the infrastructure that supports them are paid for with federal funds allocated to the Executive Office for Immigration and Refugees (EOIR), not with fees or direct charges from migrants. Although there are fees associated with certain procedures, these funds are not used to finance salaries or the core operations of the courts.

In that context, EOIR is the primary and sole entity authorized to appoint immigration judges using the federal funding it receives annually. These individuals are not “judges of the judiciary,” but rather officials of the Department of Justice selected through a process that includes public calls for applications, a review of legal qualifications, and approval by the Attorney General. No other independent agency, state or federal, is authorized or has the capacity to hire immigration judges to operate within the immigration court system.

It is important for you to know that outside of the EOIR, there are other figures related to immigration control such as asylum officers, administrative judges within DHS or adjudicators from USCIS, but none of them perform functions equivalent to those of an immigration judge nor do they have the authority to issue deportation orders.

Political decisions and budget constraints are stifling immigration courts

Migration Policy report reveals that the current situation is also partly due to recent policy decisions that have deepened the crisis. For example, the One Big Beautiful Bill, passed in 2025, limited the number of immigration judges to 800, even though independent analysts had estimated that at least 100 were needed. They needed about 1,300 to reverse the delay.

Similarly, during 2025, the administration reduced its use of discretionary tools that previously helped to alleviate the burden on the system and promoted expedited procedures that, in practice, avoid full hearings and hinder the presentation of evidence.

The administration has also reduced access to legal services. Since January 2025, EOIR has issued cease and desist orders and terminated contracts for legal service providers that operated Immigration Court Legal Assistance Centers and Legal Guidance Programs, which advised non-citizens attending court hearings, in addition to canceling other programs that provided legal advice to unaccompanied minors.

How many judges do the US immigration courts currently have?

By 2025, the number of judges had fluctuated between 600 and 700, according to EOIR, but the system faced layoffs and term terminations, vacancies, and allegations of politicization by the Department of Justice.

(https://www.justice.gov/eoir/office-of-the-chief-immigration-judge)

In the last 10 months, according to the Immigration Forum, more than 125 judges have left due to dismissals and voluntary resignations, representing an 18% decrease compared to the 700 judges projected by early 2025. In September alone, 24 immigration judges were dismissed, including one in Seattle, hired during the Biden administration.

Although the Executive Office for Immigration and Naturalization (EOIR) added 36 new immigration judges in 2025, distributed across 16 states and assigned, in part, to historically overburdened courts like those in Illinois and Massachusetts, this reinforcement comes while the system remains under enormous pressure. Meanwhile, states with the highest immigration demand and the largest backlogs, such as Florida, Texas, California, and New York, each have tens or hundreds of thousands of pending cases. Florida has more than 454,000 pending cases; Texas, around 427,000; California has approximately 327,000; and New York has over 322,000.

(https://forumtogether.org/article/legislative-bulletin-friday-october-31-2025/)

Key states lose judges, exacerbating the immigration system crisis

In 2025, several states saw reductions in their immigration judgeships, further weakening the system. The most significant case occurred in Texas, where at least five judges were removed from their posts in Houston, Laredo, and El Paso.

In California, the Sacramento court reported the departure of three judges, according to local stations affiliated with the Department of Justice. Utah also experienced cuts, with the removal of two judges. These are in addition to layoffs and departures reported in New York, Maryland, Florida, and Washington. Although the Department of Justice does not systematically publish an official breakdown by state, the pattern observed during the last months of 2025 indicates a process of reduction with direct impacts on the operational capacity of immigration courts nationwide.

The states that bear the greatest weight of the migration backlog

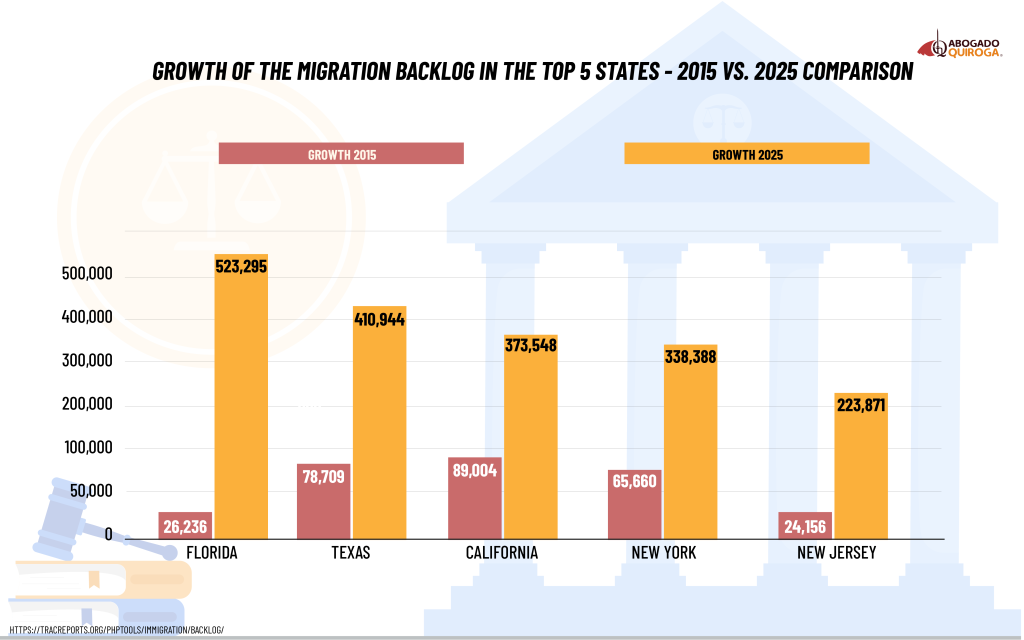

Florida has become the state with the highest number of accumulated cases during 2025, totaling 523,295. pending cases, that is, 14 % of the national total. They are followed by Texas (410,944), California (373,548), New York (338,388) and New Jersey (223,871).

Florida went from 26,236 cases in 2015 to 523,295 in 2025, representing an increase of 1,894 % in ten years. Texas went from 78,709 in 2015 to 410,944 in 2025, registering a 422 % increase. California had around 89,000 cases in 2015 and registered 373,548 in 2025, marking an approximate growth of 320 %.

New York went from having 65,660 backlogged cases in 2015 to 338,388 in 2025, representing a 415 % increase in ten years. And in New Jersey, the backlog rose from 24,156 in 2015 to 223,871 in 2025, an 826 % increase.

Record waiting times

Regarding processing times, migrants today must wait longer than in 2015 for their immigration status to be resolved. The national average wait time from the time a Notice to Appear (NTA) is received increased from 642 days in 2015 to 718 days in 2025, with peaks of over 900 days in 2021.

In contrast, between 2022 and 2024, average wait times fell, even by almost 24% in 2023, which many attributed to mass case dismissals or internal adjustments in judge assignments. However, the rebound in 2025 suggests that the relief was temporary and that the pressure on the courts not only persists but is intensifying.

The weight of asylum in the crisis

During the last decade, asylum in the United States has undergone an unprecedented transformation due to the number of cases filed and, especially, the volume of pending applications.

Between 2015 and 2025, the increase in backlogs is evident. While in 2015 the number of pending cases was around half a million, by 2024 it had already surpassed two million, and by June 2025 it had reached 2.4 million, according to the latest records. This trend accelerated significantly from 2021 onward, coinciding with changes in migration patterns, greater influxes of applicants, and an administrative structure that did not grow at the same pace.

Immigration court cuts asylum granting fees in half

According to the most recent study by TRAC Immigration, the asylum grant rate in Immigration Courts has fallen by nearly 50% over the past twelve months. In August 2025, only 19.2% of applicants were granted asylum, compared to 38% a year earlier, in August 2024. (https://tracreports.org/reports/766/)

Immigration courts are already overwhelmed, and these and other studies conclude that the system has been operating well below capacity for years. Furthermore, the human capital, judges and other staff, as well as its structural capacity and resources, are clearly insufficient.

We could conclude, then, that the crisis in the immigration courts of the United States is not a sudden phenomenon, but rather the result of a structural deterioration that has accumulated over decades and has been accelerated by recent policy decisions. The system is currently operating with historically heavy workloads, limited resources, and an insufficient and ever-shrinking pool of judges, unable to respond to a volume of cases that is growing at unprecedented levels.

Fewer judges mean a larger backlog, and a larger backlog implies greater pressure, burnout, and resignations within the system itself. The immediate consequence of all this is that millions of people must live for years in uncertainty, without a definitive answer about their future, while the immigration justice system loses its capacity to guarantee efficient and reliable processes.