The immigration policies promoted by Donald Trump’s second administration have had effects that transcend headlines and borders, and I can safely say that the most silent impact is felt within the classroom.

The tightening of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids and pressure on immigrant communities are disrupting school attendance patterns in districts across the country, especially those with high concentrations of immigrant, Hispanic, or undocumented students.

Immigrant families are under double pressure: keeping their children in the classroom while navigating the constant fear of deportation or family separation. Empty desks aren’t just due to illness or moving, but to fear. Therefore, in this special investigation, I will delve into this reality and provide an overview of the current situation in the country.

I’ll start by presenting a fact that will allow us to understand the panorama: a recent study by the Stanford Economic Policy Institute (SIEPR) documents a 22 %, as of June, an increase in school absences, specifically in California districts, which have been exposed to stricter enforcement of immigration law.

This finding is consistent with the data I analyzed in this research, which cross-referenced arrest data from ICE, the Kaiser Permanente Foundation (KFF), and the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

X-ray of immigrant students

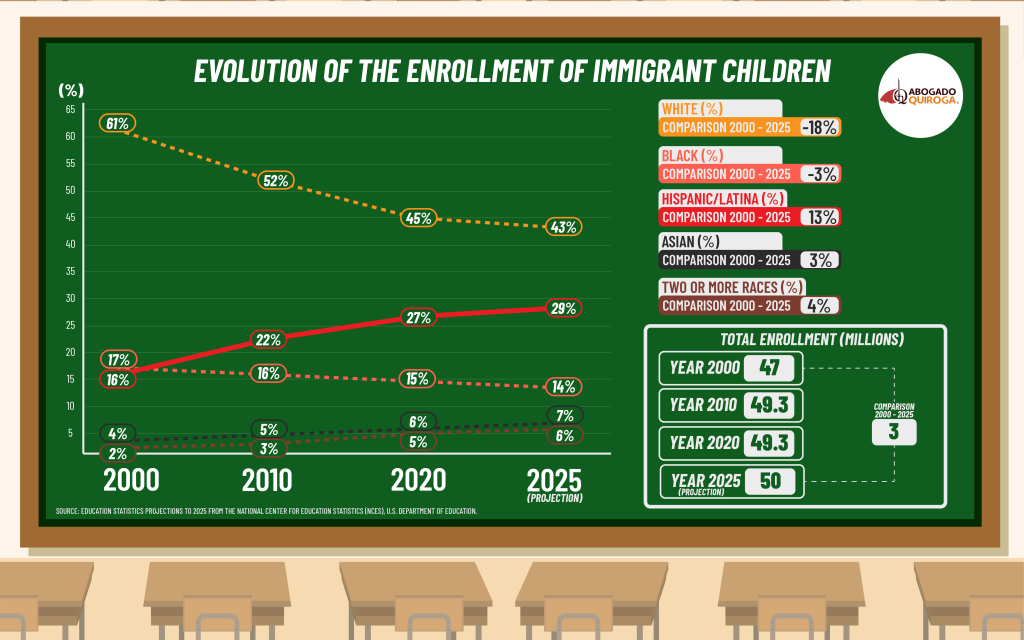

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Projections of Education Statistics, by the end of 2025, the US public school system will have around 50 million students, with an increasingly diverse composition within the students: Hispanics or Latinos will represent between 28% and 29%, compared to 16% in 2000, which clearly shows an increase of more than 12 percentage points.

In this demographic context and according to the most recent Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Education and Health Survey, approximately 5.5 million school-age children belong to immigrant families, reflecting the growing weight of this population in American classrooms.

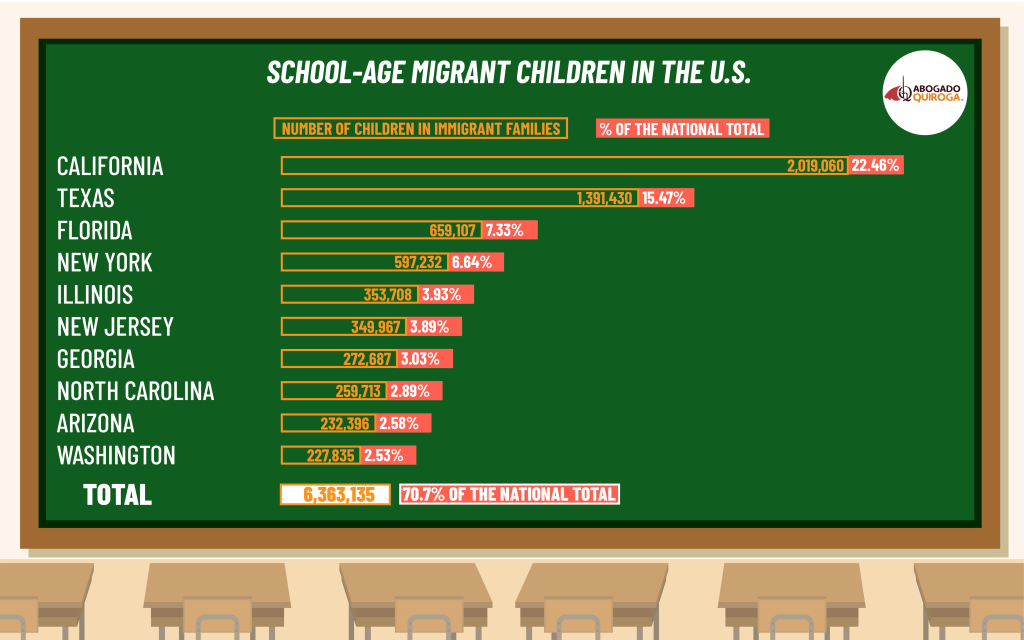

Data from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Education and Health Survey (KFF, 2025) show that nearly 9 million school-aged children between the ages of 5 and 17 are part of immigrant families. in the United States. Although the proportion varies widely between states, the phenomenon shows a clear geographic concentration in the South and Southwest:

- California and Texas top the list with 22% and 15%, respectively, of the national total, reflecting their long history as migration focal points, as well as their demographic weight.

- Florida and New York, with 7% and 6% respectively, also account for a significant proportion, confirming the importance of these states as migration corridors.

- In contrast, states in the center of the country and those far from the border have much lower participation rates, including North and South Dakota, Montana, Maine, Vermont, Wyoming, Alaska, and Mississippi, where the impact of migration on the education system is limited.

Raids and school fear: the other cost of immigration policy

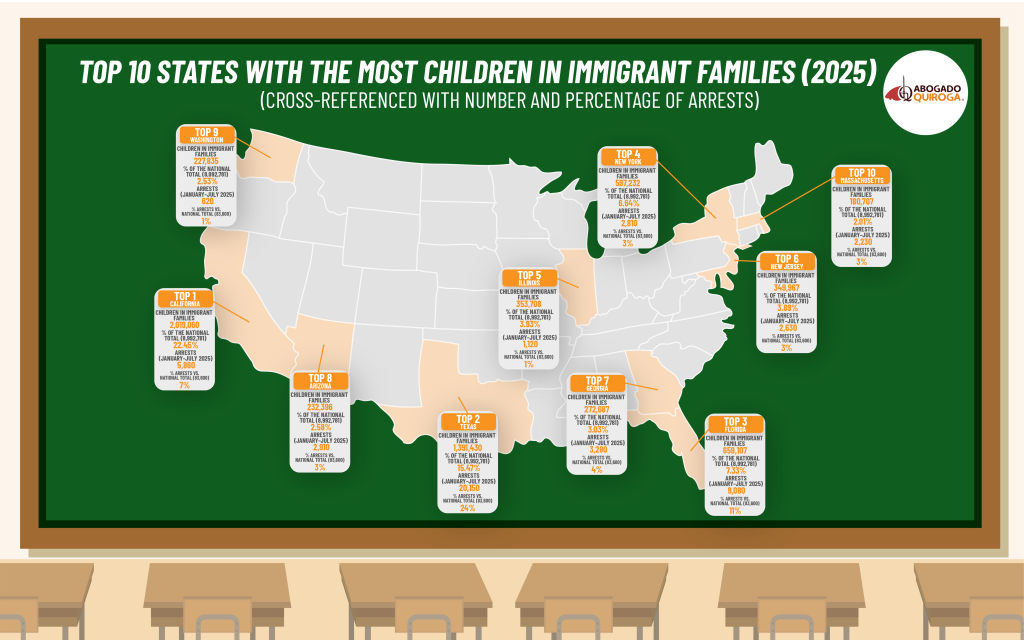

The link between immigration enforcement and school attendance has become increasingly evident. According to the Deportation Data Project, between January and August 2025, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) made 77,740 arrests, concentrated primarily in Texas (20,150), Florida (9,080), and California (5,860).

While the figures may appear purely police-related, their effects are reflected in the classroom. As I noted at the beginning of this investigation, the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) showed that, so far in 2025, in districts with high ICE activity like California, school attendance among Latino students fell by up to 22%, compared to areas without raids.

If we compare these figures with data on school-age children living in immigrant families, important findings emerge:

- California, Texas, and Florida account for 45% of all immigrant children in the country and, at the same time, 42% of national arrests, demonstrating a direct relationship between immigrant population concentration and enforcement activity.

- California has the largest immigrant child population (22 %), but a moderate arrest rate (7 %), indicating lower arrest intensity.

- Texas has the highest ratio of arrests to its number of immigrant children: 24 % of arrests with 15 % of the immigrant child population.

- Washington appears among the 10 with the most immigrant children, but with a low incidence of arrests (1 %), which could reflect a more protective state policy or less ICE activity.

Other states with high numbers include Georgia with 3,280, Virginia with 2,820, Tennessee with 2,580, and New York with 2,810. This shows that raids are no longer limited to border areas, but are also spreading to other U.S. states, albeit to a lesser extent.

These patterns allow us to deduce that ICE raids not only affect detained immigrant adults but also produce invisible or under-reported effects in schools, such as fear of deportation for parents or recurring absenteeism.

Recent data from the School Pulse Panel from the National Center for Education Statistics reinforce this connection: 70% of public schools reported an increase in absences during the 2024–2025 school year, especially for “unnecessary absences” which may be motivated by caution or fear of possible encounters with ICE.

Fear, a new variable in the US education sector

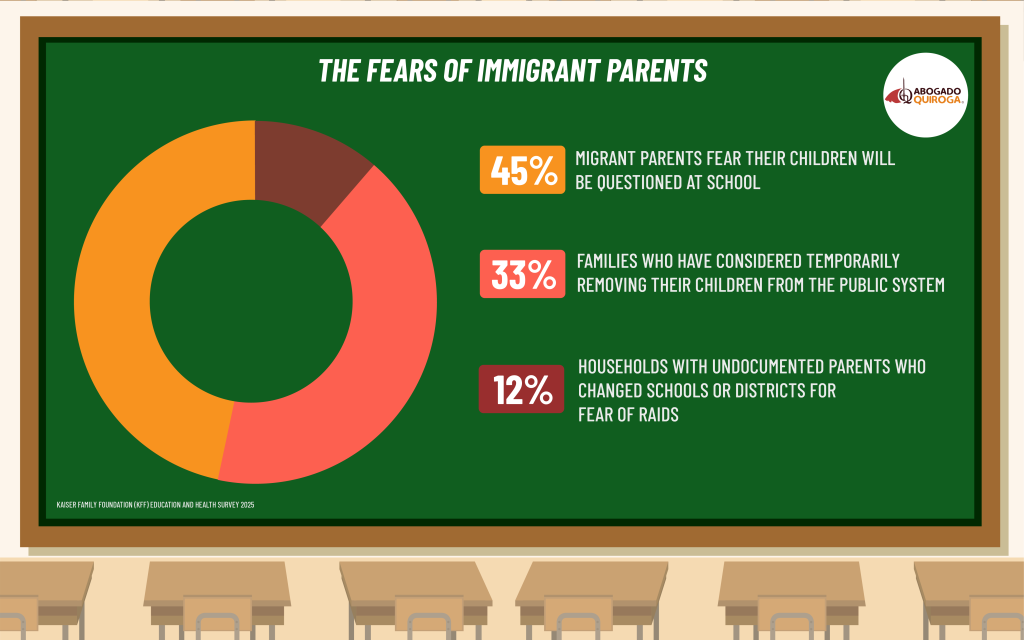

Added to this snapshot is another fact that allows us to understand the magnitude of the problem: the results of the 2025 Education and Health Survey reveal how fear of immigration policies is altering everyday decisions in thousands of homes and influencing school dynamics.

On the one hand, 45 % of migrant parents fear their children will be questioned or singled out at school because of their or their family’s immigration status. This fear, more than symbolic, undoubtedly translates into constant vigilance: parents may avoid school gatherings, children skip school as a precaution, and entire communities live on alert.

Even more worrying is that one in three immigrant households (33 %) has considered temporarily removing their children from the public system as a self-protection mechanism, and 12 % of families with undocumented parents have already changed schools or districts to reduce their exposure to raids or notifications from immigration authorities.

These figures show that fear has become an educational variable, albeit invisible or under-reported, latent in the daily lives of immigrant children and adolescents, a variable that affects their attendance, emotional stability, and academic performance.

School attendance stagnates, with southern states reporting the largest increase in absences.

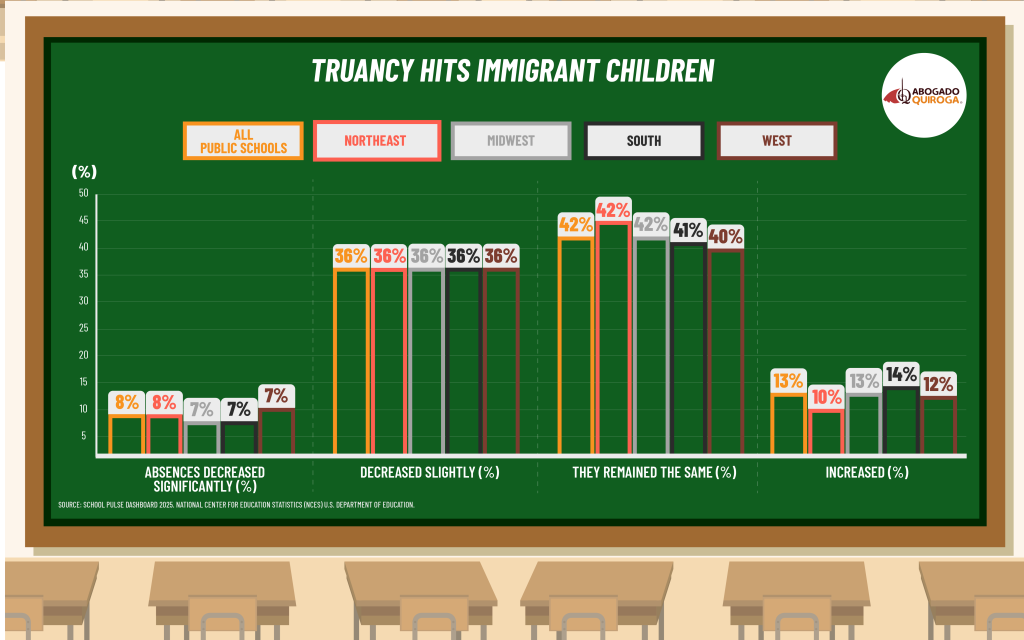

Although 44 % of the nation’s public schools reported a slight improvement in attendance through 2025, data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reveals that the recovery is uneven.

Thirteen percent of districts report an increase in absences, and the figure is slightly higher in the Southern states at 14 percent, a region that has the highest levels of immigration enforcement and concentrations of immigrant children.

The West, home to states like California, Arizona, and Nevada, shows a mixed trend: 10 % of centers reported a sharp decline in absences, while 12 % report that they persist.

In contrast, the Northeast reports the most stable performance, with 45 % of schools where attendance «remained the same,» reflecting educational environments less exposed to migratory pressure.

What data from the National Center for Education Statistics confirm is that school absenteeism is not only a response to academic or health factors, but also to the political and immigration climate; the regions with the most raids or anti-immigrant rhetoric are also those with the greatest declines in school attendance.

A new face in American schools

Between 2000 and the projections for 2025, U.S. public schools have undergone a profound transformation in their ethnic and racial composition. Although total enrollment grew from 47 to 50 million students, a modest increase of 6.4%, the internal change in the distribution of groups is markedly structural.

The percentage of white students dropped significantly, falling from 61 % to 43 %, a decrease of 18 percentage points and marking the end of a historic majority. The Black population also decreased slightly, from 17 % to 14 %, reflecting a stagnation in their relative participation.

In contrast, the Hispanic group is the main driver of change . Latino students increased from 16 % to 29 % in 25 years, an 81 % growth that consolidates them as the fastest-growing community in the education system. Furthermore, students who identify with two or more races have tripled their representation, rising from 2 % to 6 %, a phenomenon that reflects the rise of multicultural families and the greater acceptance of diverse identities.

In short, between 2000 and 2025, enrollment barely changes in volume, but its composition is redefined: the American classroom goes from being predominantly white to a multicultural and multiracial structure , where Hispanics emerge as the new growing majority .

Meanwhile, from 2020 to 2025, the proportion of white students fell from 45 % to 43 %, while the Black population fell from 15 % to 14 %, demonstrating a slower decline than in previous decades. Conversely, the proportion of Hispanic students grew from 27 % to 29 %, confirming their role as the fastest-growing group. The result is an education system that maintains its overall size, but in which traditionally minority groups continue to gain ground.

Migratory borders are also felt in the classrooms

The immigration policies implemented during 2025 have had effects that transcend headlines and borders, but as an immigration lawyer, I could say that the most silent impact is felt within the classroom.

The invisible effect of ICE raids is measured not only in numbers, but in silences: in empty desks, in children who stop participating for fear of being singled out, or in families who change residence without warning to avoid being tracked.

School districts in Texas, Florida, and California, the same states where ICE has concentrated on many of its operations in 2025, with 20,150, 9,080, and 5,860 arrests respectively, according to the Deportation Data Project report, significant fluctuations in attendance and a school climate marked by uncertainty.

This phenomenon also has a statistical dimension. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s (NCES) School Pulse Dashboard, as of 2025, 70 % of public schools reported that students were absent more than usual during the year, often due to minor symptoms or being kept home unnecessarily, reflecting how fear and family tension exacerbate an already existing absenteeism problem.

A recent analysis by the Stanford Economic Policy Institute (SIEPR) documents a 22 % increase in school absences. in the state of California exposed to stricter immigration enforcement, suggesting a direct correlation between the intensification of raids and the decline in school attendance.

It is no coincidence that the states with the highest number of ICE operations like Texas, Florida, and California, also have the largest number of school-age children living in immigrant families: 2 million in California, 1.39 million in Texas, and 659,000 in Florida, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

When both variables are combined, the correlation is clear: the states with the most immigration operations are also those that report the greatest parental fears and high variability in attendance.

Behind every number is an untold story: that of a child or adolescent who misses school because their family is afraid, that of the teacher who notices empty desks, or that of the parent who hesitates to send their child to school.

Immigration raids not only separate families, they also disrupt dreams. Fear has entered the classroom and is leaving traces that cannot be measured only in numbers, but in silence. No policy should result in a child stopping learning out of fear.