Artificial Intelligence (AI) is redefining immigration surveillance in the United States; I’ll tell you all the details in this investigation.

Contenido

The technological expansion of the Trump administration’s security agencies, especially the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), is redefining immigration surveillance in the United States.

This effort, initially aimed at improving operational efficiency, has transformed into a digital monitoring network powered by artificial intelligence, capable of tracking, identifying, and classifying millions of people inside and outside the United States.

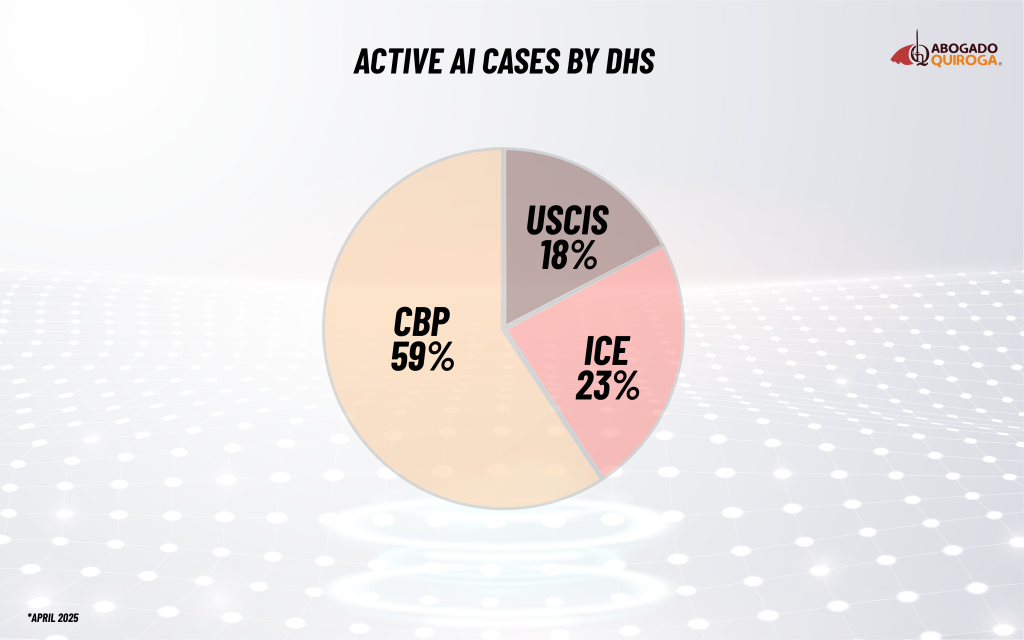

According to the investigative website Visa Verge, an official DHS document lists over 100 active AI functions within the agency: 59 are led by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), 23 by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and 18 by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). These functions encompass border surveillance, fraud detection, visa processing, and asylum screening, among others.

According to the AI Use Case Inventory, ICE currently operates more than twelve artificial intelligence systems (applied in 23 procedures) and is evaluating another list of emerging applications. These include facial recognition technologies, predictive analytics, mobile tracking, social media monitoring, and automated chatbots capable of processing immigration information.

AI is already present throughout the system and is key in many of the steps that determine who stays in, enters, or leaves the United States. For this reason, I undertook the task of analyzing the capabilities of each AI and how it impacts the daily lives of migrants.

Among the tools already in operation and supporting the operation are: PenLink , capable of linking social media data with geolocation derived from mobile phones; ImmigrationOS , which centralizes biometric and immigration information in real time; and Mobile Device Analytics, which can extract movement patterns from seized devices.

AI tools that are transforming immigration enforcement in the US.

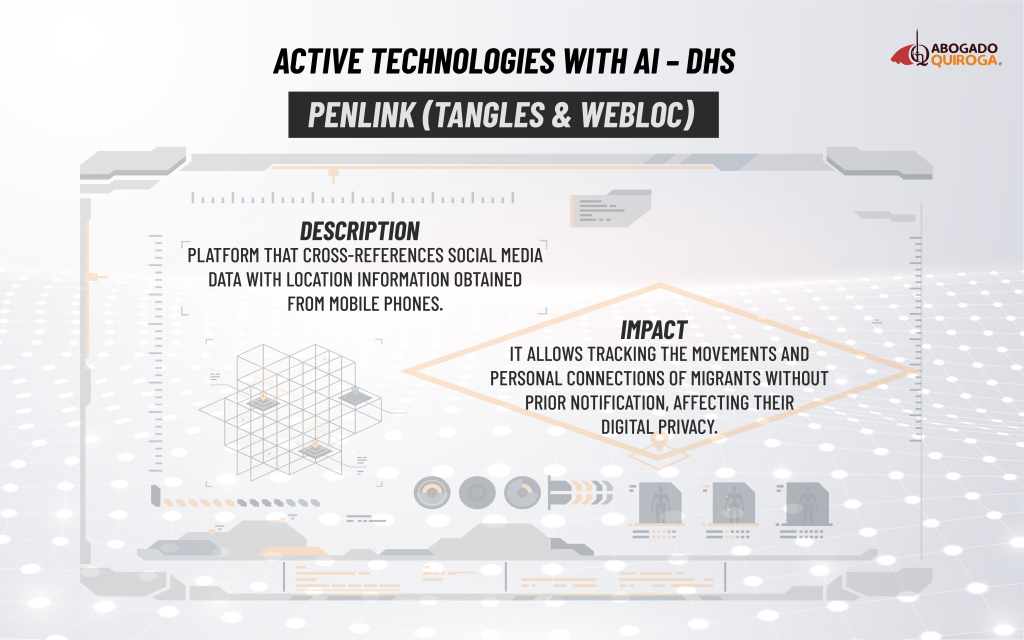

PenLink (Tangles & Webloc ) is primarily used for social media surveillance and cross-geolocation. This platform is used by ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) division and integrates tools like Tangles and Webloc, which link social media data with location information obtained from mobile phones.

In practice, this system can map personal relationships, travel routes, and behavioral patterns from posts, call logs, and business geolocation data.

This means that people going through immigration processes could be monitored without their knowledge, as authorities can review digital activities unrelated to crimes. This would give ICE greater capacity to track migrant communities or “networks.”

PenLink: the tool that can map the digital life of an immigrant like Maria

Maria, a 32-year-old Mexican mother, has lived in California for eight years without legal status. She works in agriculture and shares photos of her son on his way to school, among other personal stories, on Facebook every day. She also uses WhatsApp to coordinate jobs and receive information about new work opportunities.

One day, Maria accepts an invitation to a Facebook group to support other migrant mothers in her neighborhood. There, she shares the address of a park where they usually meet and mentions that she always takes the same route after work to avoid traffic.

Although Maria has no criminal record and is not involved in illegal activities, tools like PenLink could:

- Cross-referencing your social media posts with business location data obtained from apps on your phone.

- Identify the places he frequents: his home, his child’s school, the houses where he works.

- Identify people she communicates with frequently, including other undocumented mothers.

- To build a map of her daily routine and support network, without her knowledge of it.

Maria never had direct contact with authorities, but her digital life (posts, messages, and location data) was enough to turn her into a profile that was tracked. This creates an environment where fear exists not only on the street or at work, but also online, and where every post or message can feel like a risk.

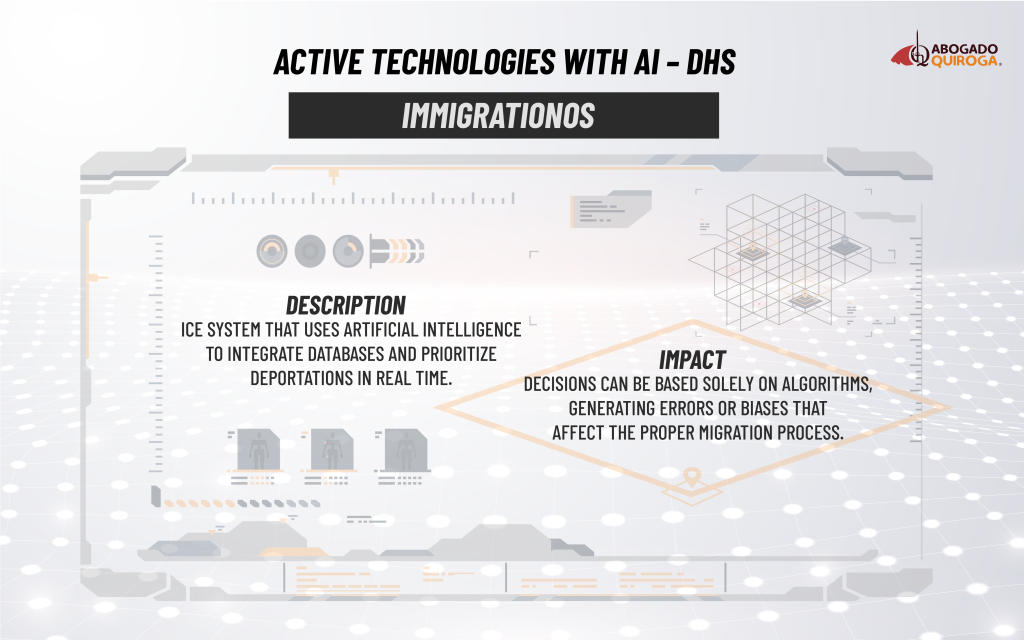

ImmigrationOS : Algorithmic management of deportations

This technology allows ICE to have a “real-time view” of the immigration system. The platform integrates databases of administrative cases, biometrics, criminal records, and immigration status, using algorithms to prioritize individuals considered “high-interest,” such as those whose visas have expired or who are in the process of voluntary deportation.

The risk to the immigrants is the excessive automation of decisions supported by algorithms that could generate risks by mispronouncing them and classifying them negatively without the possibility of reviewing or challenging their case.

Jose, and how ImmigrationOS ended up marking him

José, a 38-year-old Mexican man, lives in Texas on an agricultural work visa that expired a few months ago. He is in the process of voluntary deportation while his immigration lawyer tries to find a legal alternative so he can stay.

He never downloaded or “accepted” any immigration app. But even so, ImmigrationOS ended up tracking him. How? When Jose submitted his initial visa application, he left fingerprints, address, work history, and biometric data. When his visa expired, his case entered the ICE system, and once he requested voluntary departure, his file was updated again.

With each of those steps, your data was automatically transferred to ImmigrationOS , which connects:

- Visa databases

- Immigration records

- Biometrics

- Entry and exit history

- Active immigration orders and procedures

In other words, José didn’t find the app; the app found him because he’s part of the immigration ecosystem. One morning, without any warning, the algorithm prioritized his case because his visa had expired, he was still in the country, and his immigration process was active. Although he hadn’t committed any crime, ImmigrationOS flagged his case as «urgent» based on automated, not human, criteria.

Social Media Surveillance Team: 24/7 social media monitoring

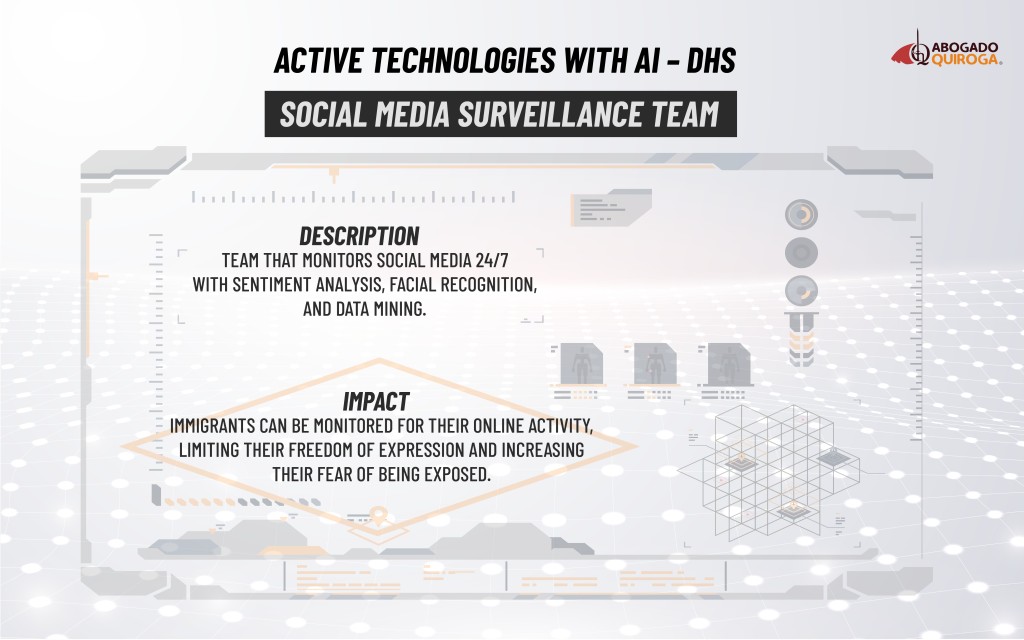

ICE plans to recruit a social media surveillance team from among analysts and contractors specializing in OSINT (Open Source). Intelligence with the aim of tracking posts on social networks such as: Facebook, TikTok, Instagram or YouTube.

This technology uses sentiment analysis, facial recognition, and text analysis tools to identify potential threats, locations, or connections between migrants. Non-citizens could be exposed through their digital activity, as public content or seemingly insignificant messages could be interpreted as «indications» of risk.

Ana and the “suspicious digital ecosystem”

Ana, a young Salvadoran woman with Temporary Protected Status (TPS) living in California, uses TikTok to learn English and Facebook to follow pages in her community. Amid the current climate in the United States, where social media is under scrutiny for misinformation, protests, and political rhetoric, Ana posts a video talking about her experience as an immigrant and the importance of protecting those who have built a life in the country. She doesn’t use aggressive language or call for mobilization; she simply tells her story. However, ICE’s new social media monitoring team, using sentiment analysis, facial recognition, and network tracking tools, flags her post for including terms like «immigrant» and «rights» at a time of heightened political sensitivity.

The system cross-references her name with public databases and notes that her status is temporary. It then identifies her face in photos from community meetings and labels her for “further observation,” mistakenly interpreting that she might be part of a broader activist network. Ana will never be notified. She did nothing illegal, but she is now under a digital risk profile that could influence future reviews of her immigration status. In this environment, the digital lives of migrants cease to be a personal space and become a terrain where an everyday opinion can be seen by an algorithm as a red flag.

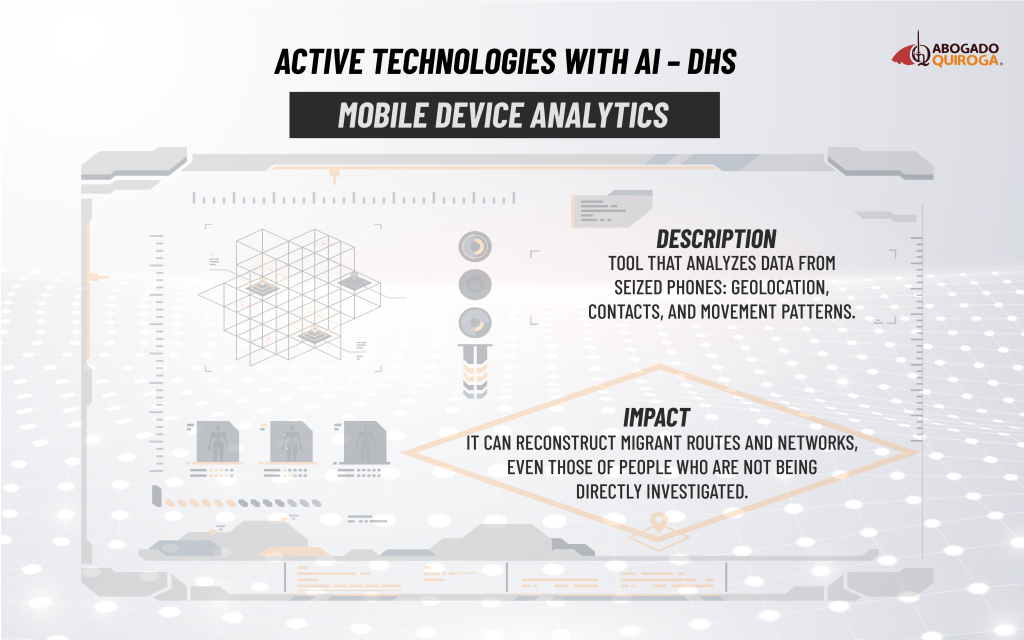

Mobile Device Analytics for Investigative Data: movement tracer

Mobile Device Analytics can extract and analyze data from mobile phones seized under court order. The system aggregates geolocation information, contacts, and movement logs to detect patterns (for example, locations where multiple devices coincide).

In migratory contexts it can be used to identify transit routes, contacts or family members.

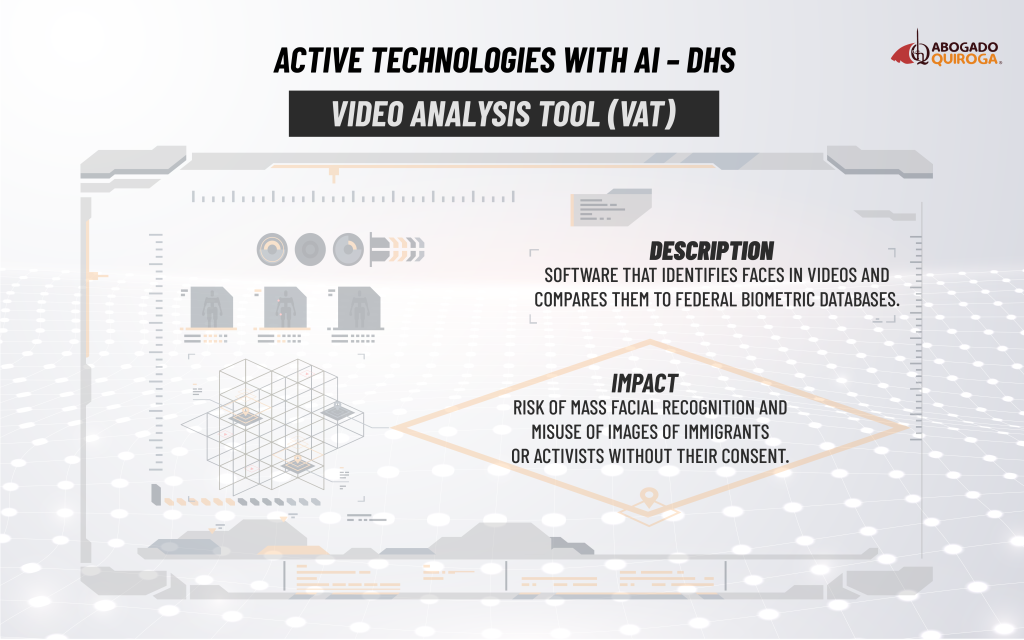

Video Analysis Tool (VAT): facial recognition

The VAT (Video Analysis Tool) could analyze videos and extract faces, comparing them with biometric databases or with information shared by other agencies.

Although the DHS reports that it is “inactive,” its records show an interest in implementing computer vision for mass identification tasks.

These types of systems can be used to identify protesters, witnesses, or people in public videos, even without their consent, affecting the rights and freedom of expression of migrant communities.

Biometric Check – in for ATD-ISAP (SmartLINK): remote facial control

This technology is already being implemented under the Alternatives to Detention (ATD) program and allows certain immigrants to remain free while their cases are being resolved. ICE uses the SmartLINK app to enable people to complete facial recognition check-ins via their cell phones.

The system compares the user’s facial image with the one stored in the DHS database, verifying their identity in real time. Although supposedly a «humanitarian» alternative to detention, in practice it is a form of constant, digitalized surveillance, as migrants must comply with frequent notifications and their location is constantly exposed. This can generate stress and a feeling of being under constant surveillance.

GRAPH 2

These technologies create a modern digital migration surveillance ecosystem that allows ICE to expand its operations and control at a time when the government’s priority is immigration policy.

While some of these applications seek to optimize administrative tasks, others, as I detailed in the examples, could directly affect due process and the civil rights of people who are in immigration custody or supervision.

How artificial intelligence has transformed immigration enforcement in the US.

The application of AI and automated technologies in immigration matters in the United States is not new and has evolved under different administrations, going from identification to prediction, ceasing to be just technical support (processing fingerprints or photos) to a tool to anticipate risks, classify immigrants and automate administrative decisions.

Currently, immigration monitoring programs integrate geolocation, behavioral analysis, and facial recognition, consolidating a «360 surveillance» model framed within national security.

It is worth highlighting that during Barack Obama’s administration (2009–2017) , the technological infrastructure that would later enable the use of artificial intelligence in immigration matters was consolidated. By 2011, the DHS had expanded the IDENT (Automated Biometric Identification System), which integrated fingerprints and photographs of millions of people into immigration and border procedures.

data interoperability programs were established between agencies (FBI, ICE, CBP, USCIS), paving the way for massive information analysis models.

Between 2017 and 2021 (during Donald Trump’s first term), there was an expansion of automated surveillance, marking a turning point. That’s when people started talking about… AI and predictive analytics formally integrated into immigration policy and border control.

In 2018, DHS launched Project HART (Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology) , intended to replace IDENT with an AI-based biometric system capable of processing faces, irises, voice, tattoos, and movement patterns. Pilot programs for facial recognition were also initiated at airports and land border crossings by Customs and Border Protection (CBP), using algorithms trained to confirm travelers’ identities.

During the Biden administration (2021–2024) , there was what could be called a quiet regulation and expansion. During this period, the main focus shifted; it was no longer just about the functions of AI itself, but about how it was being used, and the responsibility and ethics behind those uses.

In 2022, the DHS recognized 43 cases of AI use within the Department, several associated with issues such as: border management, biometrics and detection of immigration fraud.

In addition, ICE and CBP increased their use of privately owned tools such as ( Palantir, Giant) Oak, Clearview AI) for analytical support, identity validation, and migration risk prediction. Remote monitoring algorithms were also implemented, especially in alternative to detention supervision (ATD) programs, introducing AI into the surveillance of migrant individuals on parole.

ICE is increasing its contracts in artificial intelligence and biometrics

According to The Washington Post, ICE has signed multiple contracts in recent months to expand digital surveillance, including acquisitions of facial recognition, iris scanning, and smartphone hacking tools, among others.

The investigation carried out by the newspaper establishes that ICE’s contractual obligations as of September reached $1,4 billion, the highest monthly sum in at least 18 years.

AI tools under evaluation or pre-deployment for migration surveillance

According to the AI Use Case Inventory published by the DHS in July, the agency has at least four technological programs or mechanisms in the pre-deployment, development, acquisition, or testing phase that it expects to implement or articulate to expand digital surveillance.

- The Machine Learning Translation Technology Initiative (MLTI) is a real-time automatic translation system

(speech-to-text, text-to-speech, speech-to-speech) that could facilitate communication with people who are not fluent in English. However, translation errors or cultural biases could cause complex misunderstandings, especially in interviews or sensitive procedures.

- Title III Semantic Search and Summarization for Translated Content, is a system It uses artificial intelligence and natural language processing to analyze translated texts, detect patterns, identify individuals, or detect potential fraud in investigations. The impact on migrants could be related to possible errors in interpretation or translation, unfairly linking individuals to investigations or risk profiles.

- Policy Analyst Assistant is a virtual assistant that searches for regulations, rules, and answers frequently asked questions using generative language models. While it doesn’t directly interact with people, it could influence immigration policies or institutional decisions based on misinterpretations or biased interpretations of regulations.

- Chatbots and internal administrative assistants are automated customer service tools programmed to answer questions, manage documents, or guide procedures. While they facilitate service, they could lead to errors in procedures or generate false expectations about immigration processes if the information is incomplete or incorrect.

AI and digital surveillance projects in the hands of the US Congress.

Currently, the United States Congress is considering several bills that link the use of artificial intelligence (AI) or digital surveillance to government operations. This process inevitably touches on immigration policies and border control systems.

At least four legislative projects related to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), ICE, and CBP have been introduced in the current legislative session: the AI PLAN Act (HR 2152), the PROACTIV Act (S. 2381), the Protection Against Foreign Adversarial AI Act (S. 1638), and the AI Literacy and Inclusion Act (HR 3210). While not exclusively focused on immigration, all seek to regulate or enable the use of artificial intelligence in surveillance, identity verification, and predictive analytics.

Among them is the AI PLAN Act, which requires the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of Justice, and other agencies to develop strategies to mitigate risks associated with the use of AI in sensitive operations. This includes biometric identification and digital monitoring systems applied to migrants in custody or on parole. Meanwhile, the PROACTIV Act strengthens data protection and algorithmic transparency, with a potential impact on DHS biometric databases, while another initiative prohibits adversarial AI technologies of foreign origin.

Taken together, these efforts reflect Congress’s intention to strengthen the legal and technological infrastructure that allows DHS to expand the use of AI in immigration matters. However, the discussion still leaves a central question unanswered: what guarantees of transparency, oversight, and accountability will exist to prevent abuse and protect the rights of individuals subjected to these technologies?

Cybersecurity and responsible use of AI in focus

During National Cybersecurity Awareness Month, the White House issued a proclamation recalling that earlier this year the Trump administration signed an Executive Order aimed at strengthening U.S. cybersecurity by focusing on critical protections against foreign cyber threats and improving secure technology practices.

Among other measures, this initiative directed members of the federal government to promote the development of secure software, drive the adoption of the latest encryption protocols, and refocus artificial intelligence cybersecurity efforts toward identifying and managing vulnerabilities, rather than censoring the legitimate expression of the American people.

However, the technological expansion and development of more digital surveillance in the United States has not been without criticism. An audit by the DHS Office of Inspector General (January 2025) warns that, although AI governance policies exist, the department lacks consistent control mechanisms, transparent public reporting, and independent audits of how these technological tools are used.

For their part, organizations such as Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and the Center for The Privacy and Technology section of Georgetown Law have issued warnings about a potential lack of safeguards surrounding the use of biometric and social media data. They state that the risks are numerous, as errors in facial recognition algorithms can disproportionately affect people of color, activists, and journalists, and that the misuse of such information could generate immigration “risk lists.”

All of this adds to some studies that reveal that there are more people worried than excited about the use of AI, since according to the Pew Research Center , concern about artificial intelligence is especially common in the United States, Italy, Australia, Brazil and Greece, where approximately half of adults say they are more worried than excited.