United States faces a relentless war against illegal fentanyl, as it has become the leading cause of overdose deaths in the opioid crisis. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nearly 73,000 overdose deaths in 2023 involved synthetic opioids (primarily illegally manufactured fentanyl), accounting for about 69% of all overdose deaths from synthetic drugs other than methadone. (https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/about/fentanyl.html)

Multiple studies have found that the illicit supply of fentanyl operates through a complex transnational chain, as much of its ingredients appear to come from China and are then processed in Mexico for distribution in the U.S. (https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/fentanyl-and-us-opioid-epidemic )

Various investigations and official data agree that fentanyl as a phenomenon is mostly linked to criminal networks and trade routes in which numerous American citizens are allegedly involved, and there is no evidence to support the thesis that immigrants who cross the border illegally are the main source.

What is fentanyl?

Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid that can be used to treat severe pain or in some surgeries. Most injuries and overdoses related to this drug are rooted in illegally manufactured fentanyl.

There are two types: pharmaceutical fentanyl and illicitly manufactured fentanyl. Both are synthetic (laboratory-made) opioids. The first one is used for surgery or to treat severe pain, usually caused by cancer. The second one is commonly found in powder form or compressed into counterfeit pills and can be smoked, snorted, injected, or ingested. Drugs laced with fentanyl are extremely dangerous, and many people may not know their medications contain it.

Intersecting Narratives: Border Security and Fentanyl Trafficking

Since 2016, the narrative around fentanyl has become a political tool. Candidates from both parties have used the issue to demand walls, deportations, and tougher laws. In Donald Trump’s second term, this rhetoric has intensified: migrants are no longer just «taking jobs,» they are now «bringing fentanyl.» The phrase, repeated at rallies and debates, reinforces a framework of collective guilt that obscures data and realities.

And while Trump doesn’t directly blame them for the problem, he does imply that «open borders flooded the United States with these drugs and with people who shouldn’t be in the country,» making what could be considered an explicit reference to the millions of immigrants who arrived, especially during the Biden administration.

Various studies, such as one by the Cato Institute, show that 90% of fentanyl seizures at the southern border occur at official ports of entry, and that more than 85% of those involved are U.S. citizens, not undocumented migrants. However, the association between «drug» and «immigrant» has become a cultural reflex fueled by media discourses that prioritize fear over evidence.

The result: stigmatized immigrant communities, increased raids and surveillance, and a public narrative that justifies restrictive measures under the banner of national security.

This dissonance between data and narrative reveals a deeper phenomenon: the use of fear as a tool of polarization. Linking immigrants to fentanyl reinforces a sense of constant threat, useful for justifying budgets, walls, and containment policies.

But does research support the claim?

Different studies, such as that of the American Immigration Council, conclude that most seizures occur at ports of entry where U.S. citizens are the primary parties involved in smuggling.

According to this research center, most of the fentanyl smuggling comes from people who can legally enter the United States, as they manage to evade detection by disguising themselves as normal travelers entering or re-entering the country. It is no coincidence, then, that transnational criminal organizations seek to recruit U.S. citizens, given that they are subject to fewer controls upon entry.

Data obtained by the American Immigration Council through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) confirms that many people arrested for smuggling fentanyl into the United States at southern border ports of entry are U.S. citizens. In total, 81.2% of all seizures along the southwest border (at field offices such as San Diego, Tucson, El Paso, and Laredo) between fiscal years 2019 and June 2024 were of U.S. citizens, exceeding 3,000 people. While, based on available figures, it could be deduced that the number of Mexican citizens would be around 748. ( https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/fact-sheet/fentanyl-smuggling/ )

A review of the statistics shows that the largest proportion of people caught trafficking fentanyl at U.S. ports of entry has been American citizens. For example, in 2021, the year with the highest number of arrests, approximately 850 people were American nationals, while only about 100 were Mexican nationals and another 10 were of unknown nationality.

If we analyze the year 2024, approximately 300 people were American citizens, 50 were Mexicans, and about 5 were of other nationalities.

Even agencies like the DEA have concluded in various reports that the majority of fentanyl reaching the US is controlled by transnational criminal organizations. In its most recent study (2025), the DEA states that “Official and academic evidence shows that the increase in fentanyl deaths and the circulation of fentanyl in the US are driven primarily by criminal networks (cartels and domestic distributors), not by regular migratory flows.” (https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2025-07/2025NationalDrugThreatAssessment.pdf)

But these are not the only investigations that reveal that U.S. citizens are the primary offenders for trafficking fentanyl. A 2023 study by the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that 86.4% of those sentenced for this type of trafficking were U.S. citizens. (https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/quick-facts/Fentanyl_FY23.pdf )

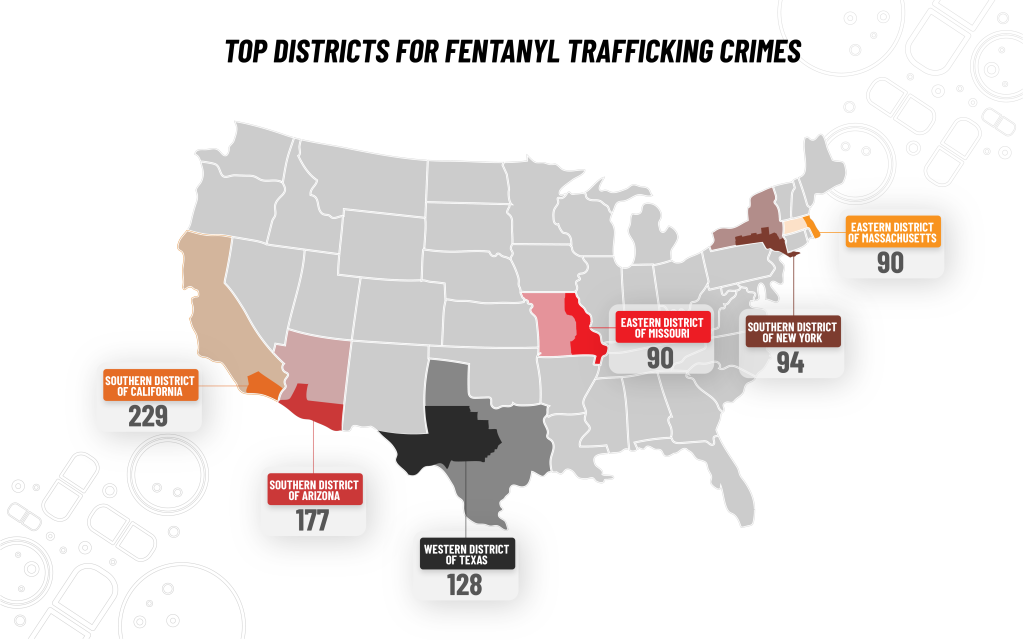

The report also reveals the top 6 districts for fentanyl trafficking offenses: Southern District of California (229), District of Arizona (177), Western District of Texas (128), Southern District of New York (94), District of Massachusetts (90), and Eastern District of Missouri (90).

Migrating and being guilty: the new face of criminalization

In the American public debate, the figure of the immigrant has become a container for national fears. The fentanyl crisis has served to reinforce this image of the foreigner as a threat. Although the Department of Justice ‘s own statistics show that many trafficking cases involve American citizens, in different contexts it continues to be repeated, without evidence, that immigrants are responsible for bringing drugs into the country. This link between migration and crime is not only false, but profoundly functional: it diverts attention from the health system and places the blame on those least able to defend themselves.

The consequences of this narrative are visible in border controls, arrests, and the everyday treatment of Latino communities. In cities across the South and Midwest, farm workers, delivery drivers, and asylum seekers are subjected to searches and pat-downs under the guise of the «fight against fentanyl.»

Furthermore, the criminalization associated with fentanyl has a silent but devastating effect: it inhibits reporting and access to health services. Many undocumented immigrants avoid seeking medical attention or reporting emergencies for fear of being detained or deported. This institutional mistrust exacerbates the problem it is supposedly intended to combat. In the name of security, an environment of fear is created that strengthens the very illegal networks that political rhetoric promises to dismantle.

Which generation is leading the fentanyl trade?

According to information released by the American Immigration Council, between 2019 and June 2024, 3,033 U.S. citizens were arrested for fentanyl smuggling. The available data we analyzed indicates that the majority are young people, between the ages of 20 and 31. Meanwhile, the average age of U.S. citizens arrested during this period for attempting to smuggle fentanyl was 30.

Meanwhile, minors under 16 years of age accumulated nearly 40 arrests during this period, 17-year-olds averaged 60, and U.S. citizens 65 years of age and older totaled nearly 60 arrests.

The data revealed by these statistics are consistent with figures from the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which reports on the immigration status of those convicted and sentenced nationwide for fentanyl trafficking. Overall, during fiscal year 2023, 86.4% of those convicted for fentanyl trafficking were U.S. citizens, and the average age at sentencing was 34.

Although the study does not provide statistics on Mexican citizens, some projections suggest that arrests of Mexican nationals would have a similar distribution, as criminal networks likely recruit similar profiles (young people) for these types of high-risk tasks.

How does fentanyl get in?

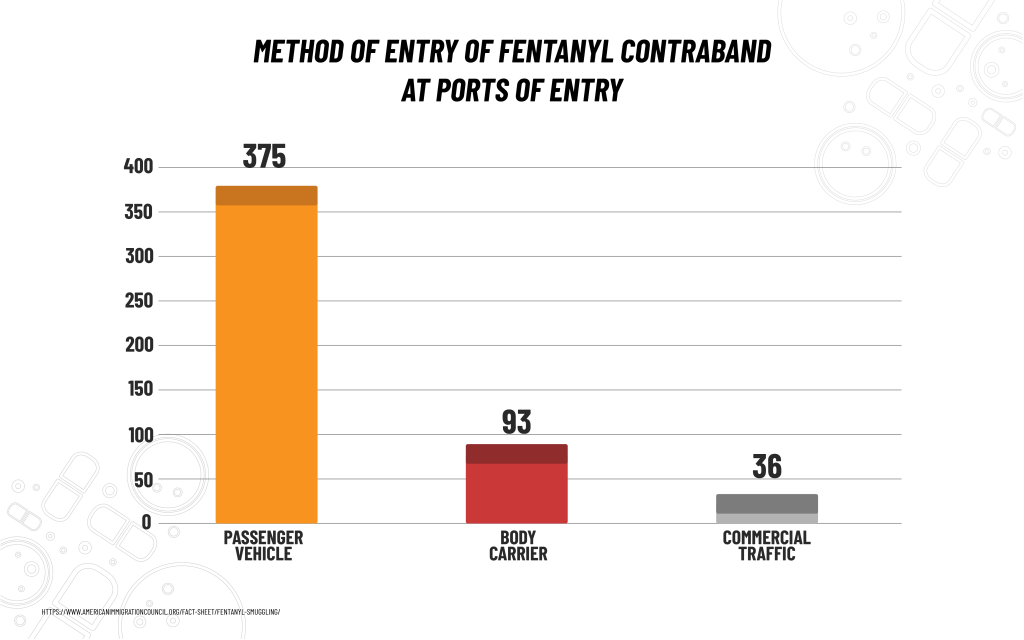

According to this study, most of the fentanyl introduced across the southern border does not enter attached to the bodies of migrants crossing the border on foot (as is often claimed), but rather in the vehicles and on the bodies of U.S. citizens and other people legally entering the United States through land ports of entry.

Figures indicate that four out of five people apprehended for smuggling fentanyl into the United States at the southern border between October 2018 and June 2024 were U.S. citizens; the remainder were mostly individuals with visas, border crossing cards, or other permission to legally enter the United States.

But despite the evidence, many Americans continue to buy into the idea that immigrants are the ones bringing the largest amount of this drug into their country.

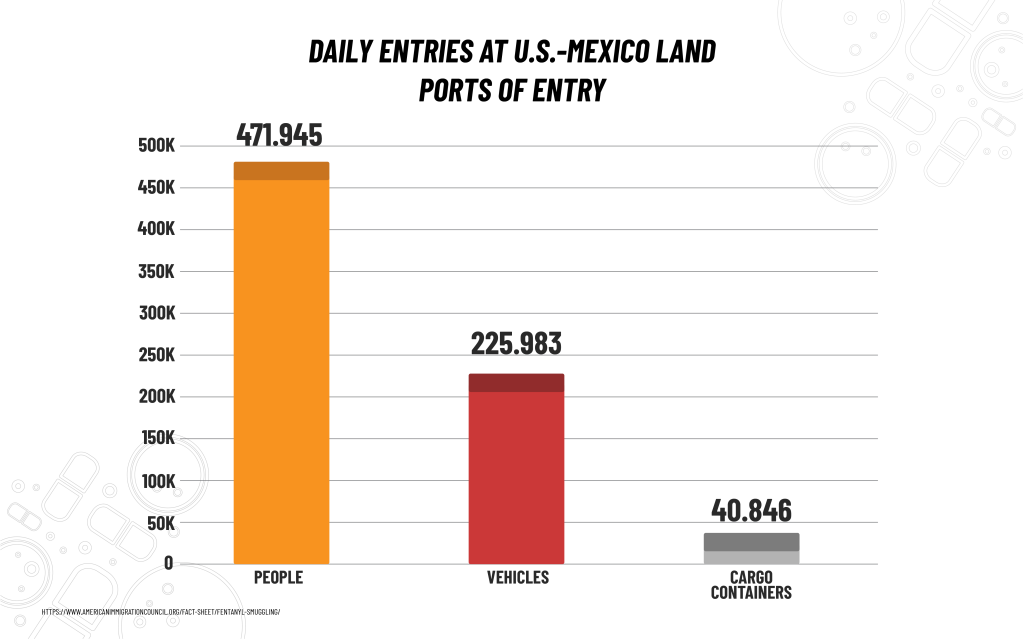

Traffickers take advantage of ports of entry because of the number of people and vehicles that cross there. For example, on an average day in March 2025, 204,241 private vehicles with 361,764 passengers crossed the border, as did 104,926 pedestrians, 21,359 trucks with 37,456 cargo containers, 352 buses with 5,255 passengers, and 31 trains with 3,390 cars.

This study also indicates that despite the significant investment in new technologies at ports of entry, most people crossing the land border are not subjected to comprehensive screening, as this would accumulate border traffic and delay the efficient movement of people and goods.

These conclusions are based on an analysis that the American Immigration Council conducted of nearly 700 press releases and social media posts published by CBP between January 2021 and March 2024. The available data, according to the researchers, allows them to track information that is not reported on official portals, such as the location of the seizure and how the fentanyl was attempted to be introduced into the United States. (https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/fact-sheet/fentanyl-smuggling/ )

Immigration or crimmigration?

This entire panorama has crossed a fine line between criminal and immigration proceedings. The criminalization of immigrants is increasingly being used to drive mass deportation policies.

As an immigration attorney, I am concerned that there is an increasingly evident fusion between criminal law and immigration law, which has evolved into new terms and fields of study such as crimmigration , a term that describes the growing tendency to criminalize immigrants by merging criminal and immigration laws.

Fentanyl seizures over the years

Available statistics allow us to conclude that fentanyl seizures have been progressively increasing over the years, except for fiscal year 2025. Between fiscal years 2017 and 2020, there was a gradual increase from 2,500 pounds to 4,000 pounds, for a total of 12,100 pounds over those four years. In 2021 and 2024, seizures skyrocketed, from 12,000 pounds to 22,000 pounds, for a grand total of 76,000 pounds seized over those four years.

As of August 2025, the government has seized just 11,500 pounds of fentanyl, a little more than half of what was seized in 2024. This could indicate that fewer traffickers are trying to bring this drug into the United States, or that despite their efforts, criminals are gaining ground with new strategies.

Is the Trump 2.0 administration succeeding in reducing fentanyl trafficking in the US?

Even though US border agencies have increased operations and have been given more funding, seizure figures are falling alarmingly, for example: during fiscal year 2023 , according to CBP statistics, 27,000 pounds of fentanyl were intercepted, a figure that by 2024 dropped to 21,900 lbs. and in 2025 barely reached 11,500 lbs. (https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/frontline-against-fentanyl )

What can be concluded from some of the data available from CBP is that this administration has seized smaller quantities of fentanyl than the previous administration, and that its crackdown is not being reflected in the number of pounds seized.

If we look at the total pounds of fentanyl seizures between the years 2023 and 2025, we find that the Trump Administration has seized -134.8% compared to the fiscal year 2023. If the analysis is done with the immediately preceding year (2024), we can also see that the difference is -90.4%.

Analyzing the figures specifically between the months of February and August of the last three years, we find that this administration has seized -191 % compared to the same months in 2023. If we compare the same months with 2024, the percentage also reaches -110 %. While in 2023 up to 2,900 pounds of fentanyl were seized in a single month, and in 2024 up to 2,800 during the month of July, in 2025 the record is 1,400 pounds for the month of July, the remaining months only exceed an average of 700 pounds seized.

Is the Trump administration 2.0 succeeding in reducing fentanyl trafficking in the US or just restricting migration?

Despite increased operations and increased resources for U.S. border agencies, fentanyl seizure figures show a significant decline. During fiscal year 2023, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported seizing 27,000 pounds of fentanyl; in 2024, the figure dropped to 21,900, and in 2025, it barely reached 11,500. ( https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/frontline-against-fentanyl )

Some analysts have suggested that this decline could be partially related to the reduction in irregular migration flows following the Trump administration’s tightening of border policies. However, this relationship is more apparent than real: historically, most seizures do not occur among irregular crossers, but rather at legal ports of entry, where the main traffickers are U.S. citizens or people with valid immigration documents. Consequently, fewer migrants at the border do not necessarily mean less fentanyl entering the country.

Looking at the total numbers between 2023 and 2025, the Trump administration seized 134% less fentanyl than in 2023 and 90% less than in 2024. Between February and August of the last three years, the reduction reached 191% compared to 2023. While in 2023 up to 2,900 pounds were intercepted monthly and 2,800 in 2024, in 2025 the record barely reached 1,400 pounds in July.

The arguments presented and the statistics analyzed show us that fentanyl trafficking is primarily driven by criminal and logistical dynamics that have little to do with human mobility. Perhaps continuing to conflate the opioid crisis with immigration management will lead to further diversion of resources and efforts, and at the same time, greater discrimination against non-U.S. citizens.

The more investment in detection technology, international cooperation, and public health programs, the greater the chances of curbing the fentanyl problem. Continuing to criminalize migrants seems to be no way to solve the crisis.