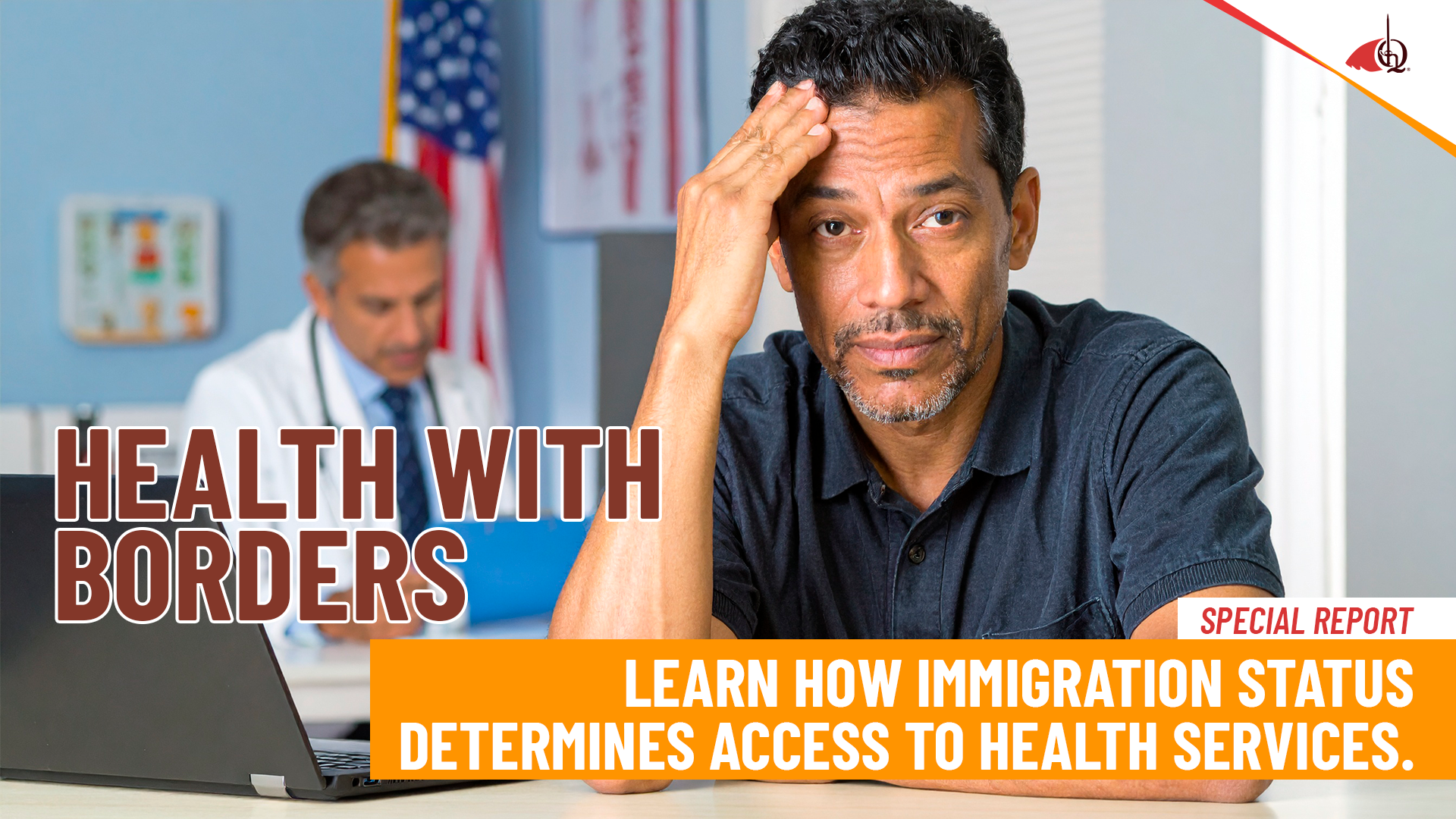

Health with Borders? Analyzing How Immigration Status Determines Who Accesses Medical Services in the U.S.

Contenido

The U.S. health care system reflects inequalities in access to medical care, especially among the immigrant population; immigration status and residency status continue to be decisive factors determining who can have health insurance and who is excluded.

The most recent figures confirm this. According to the latest American Community Survey (ACS), 47.1 million immigrants reside in the country: 24.7 million are naturalized citizens and 22.4 million are non-citizens, including both legal and undocumented residents.

The gaps in coverage are stark, according to the Kayser Family Foundation (KFF), a nonprofit organization that researches health policies. Less than 10% of citizens, whether native-born or naturalized, lack access to health insurance, while the proportion rises to 18% among legal immigrants and reaches 50% among undocumented immigrants.

These gaps are not only due to legal restrictions that exclude them from Medicaid, CHIP or the Affordable Care Act (ACA), known as Obamacare, but also to employment factors: most work in sectors with precarious employment that do not offer health insurance.

Non-citizen immigrants are more likely to postpone medical care, receive fewer preventive checkups, and spend less on health care, not because they are healthier, but because they face greater barriers to access. This, of course, increases the risk of late diagnoses, overuse of emergency rooms, and low vaccination coverage, affecting them and public health in general.

Amid this situation, some states have implemented measures to reduce these gaps, such as expanding Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) coverage for minors and pregnant women, or funding health programs with state funds regardless of immigration status. However, these initiatives vary by state, so millions of immigrants, especially undocumented immigrants, continue to live in vulnerable situations.

In this investigative article, I seek to present a snapshot of current access to healthcare in the United States from the perspective of an immigrant: who is covered, who is excluded, what barriers persist, and how state and federal policies are shaping a scenario in which immigration status becomes an invisible barrier to exercising the right to healthcare.

What is health coverage like based on your immigration status?

Let’s get down to business. The most recent figures confirm the magnitude of inequality in access to healthcare based on immigration status. According to the KFF Foundation, 21.7% of documented non-citizen migrants in the United States lack health coverage, and the situation is even more critical for undocumented immigrants, where the percentage rises to 42.5 %. A difference that, from the outset, speaks volumes about the existing gaps between US citizens and non-citizens.

A study published by the American Medical Association ( JAMA) notes that undocumented immigrants face many barriers to accessing healthcare.

In most cases, they can only receive care in emergency situations because the law requires hospitals to treat them, but it doesn’t guarantee them medical checkups, ongoing treatment, or preventive services. This creates significant inequality between states: some, like California, New York, and Minnesota, have decided to expand coverage and provide access to more services regardless of immigration status, while others only provide emergency care and nothing else.

There are state-funded programs that help cover more people, but they depend on budget and political decisions, so they can change or even be discontinued.

In practice, many immigrants must wait until they are very ill to receive care, which increases costs and health risks. Furthermore, the emergency Medicaid program, which they use most, represents less than 1 % of total health spending, demonstrating how limited its scope is compared to real needs. Taken together, both studies show the same reality: undocumented immigrants face the greatest exclusion.

The gaps that are marked throughout the United States.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), the differences in insurance are marked: less than 10 % of citizens (native or naturalized) lack insurance, among legal immigrants, the proportion rises to 18% and among undocumented immigrants, it reaches almost 50 %.

This reflects not only legal restrictions (exclusion from Medicaid, CHIP), but also employment factors: many immigrants work in precarious sectors without access to health insurance. The figure is clear: undocumented immigrants are six times more likely to lack health insurance than native-born citizens, which puts them in a vulnerable situation.

The most recent KFF/LA Times survey of immigrants in the United States points to additional barriers such as language, discrimination, and fear of immigration:

| Barriers to Healthcare Access for Immigrants | |

|---|---|

| Type of Barrier | % Immigrants Affected |

| Unfair treatment (language, accent, status, payment) | 25% |

| Concerns not heard | 17% |

| Explanations difficult to understand | 15% |

| Disrespectful treatment by staff | 12% |

| No access to interpreter (LEP) | 17% |

| Fear of public charge | 27% avoided seeking help |

| Children of immigrants without insurance | 9% (15% in low-income/non-citizen households) |

| Preventive checkups in children | 72% uninsured vs. 87% insured |

- One in four immigrants experienced unfair treatment in healthcare services, whether due to language, accent, status, or payment method.

- 17% did not feel their concerns were heard.

- 15% received explanations that were difficult to understand.

- 12% reported disrespectful treatment from staff.

- 17% of immigrants with limited English proficiency did not have access to real-time interpretation.

Furthermore, fear of the public charge rule, a U.S. immigration rule that assesses the likelihood that a foreign national will rely primarily on government assistance for subsistence, inhibits the search for insurance or social support:

- 60% of immigrants are unaware of whether their use of social programs affects their residency.

- 27% avoided requesting assistance with health, housing, or food for fear of immigration consequences.

The map of state inequalities in health coverage

The map clearly shows That coverage for undocumented immigrants varies drastically by state, but before reviewing some of the most notable cases, it is important to explain the variables that were analyzed:

Undocumented population corresponds to number of undocumented immigrants in each state and their proportion of the national total. Example: California has 2,739,000 undocumented immigrants (24.8% of the U.S. total).

Income eligibility limits (% of FPL, Federal Poverty Level) measure the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) as a percentage. and indicates the income level up to which a person can apply. Example: In Texas, only parents earning up to 15% of the FPL are eligible; childless adults do not. In contrast, in most states with Medicaid expansion (e.g., California), the limit is 138% of the FPL. allowing both low-income parents and childless adults to be eligible.

Duration of registration and coverage is divided into 4:

- Retroactive coverage: Coverage that applies to medical expenses prior to enrollment. For example, let’s imagine Pedro had an accident in November, but only applied for emergency Medicaid in January. Since his state has three-month retroactive coverage, Medicaid can pay his medical bills for November, December, and January, even though he applied after the accident.

This is very useful because many immigrants apply after the emergency, and can still receive help covering previous medical debts.

- Prospective: This is coverage that continues after the day you applied.

Let’s use the example of Maria, who had an emergency in January in California. In this case, in addition to covering that event, the state gave her 12 months of continuous coverage. This means that if she has a checkup in April or needs another treatment in August, she’s still covered by Medicaid without having to reapply. In other states, she would have only been covered for the January emergency and nothing else.

- Emergency duration: Indicates that the insurance only pays for a specific emergency (e.g., childbirth, emergency surgery, or an accident). Once that event ends, you no longer have coverage. This is the case in Florida and Texas, where coverage is limited to the emergency event.

- Pre-application option: In some states, pre-application is allowed before an emergency occurs, which saves you time. For example, in Wisconsin and Wyoming, this option only applies to pregnant women, while in other states, this option doesn’t exist: you can only apply for coverage after the emergency has occurred.

Uneven coverage: Access and duration depend on the state you live in.

In the United States, an undocumented immigrant’s ability to receive emergency medical care depends not only on the severity of their condition, but also on the state in which they live.

The first big gap is in the income limits. In states like California, New York, and Massachusetts, undocumented immigrants with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) can access coverage. This is equivalent, in 2025, to an annual income of approximately $21,600 for a single person, or $44,400 for a family of four. This means that low-income workers, even those without children, can receive care in the event of an emergency.

In contrast, in places like Texas and Tennessee, only parents with extremely low incomes, equivalent to 15% of the federal poverty level (FPL), qualify for coverage. This means that, for this year, a single person would have to earn less than $2,350 a year (about $196 a month), and a family of four less than $4,823 a year (about $402 a month). In practice, childless adults are excluded from the benefit entirely.

The differences are also marked in the duration of coverage. In most states (37, including Alabama, Delaware, Maine, South Dakota, and Washington, DC), assistance is limited to the exact moment of the emergency. The patient must re-enroll each time they face a medical crisis. In other words, childbirth, emergency surgery, or an accident are covered, but nothing else.

Some states have opted to offer a longer respite. California, Oregon, and New York, for example, allow coverage to be extended for up to 12 prospective months, preventing people from being left unprotected after leaving the hospital. Others, such as Pennsylvania and Virginia, offer six months of coverage.

Another key aspect is the ability to apply for coverage before an emergency. This can mean the difference between life and death in critical situations. However, only two states allow this option: Wisconsin and Wyoming, where the measure is limited to pregnant women, while in most of the country, the system requires patients to first go through the crisis before seeking help.

In summary, 37 states and Washington, DC (72%) limit coverage to the date of the emergency. Only 18 states (36%) offer retroactive coverage of three to six months, allowing for the recognition of prior medical expenses, and only 13 states (25%) offer prospective coverage, extending beyond the emergency. Of these, eight offer coverage for up to a full year.

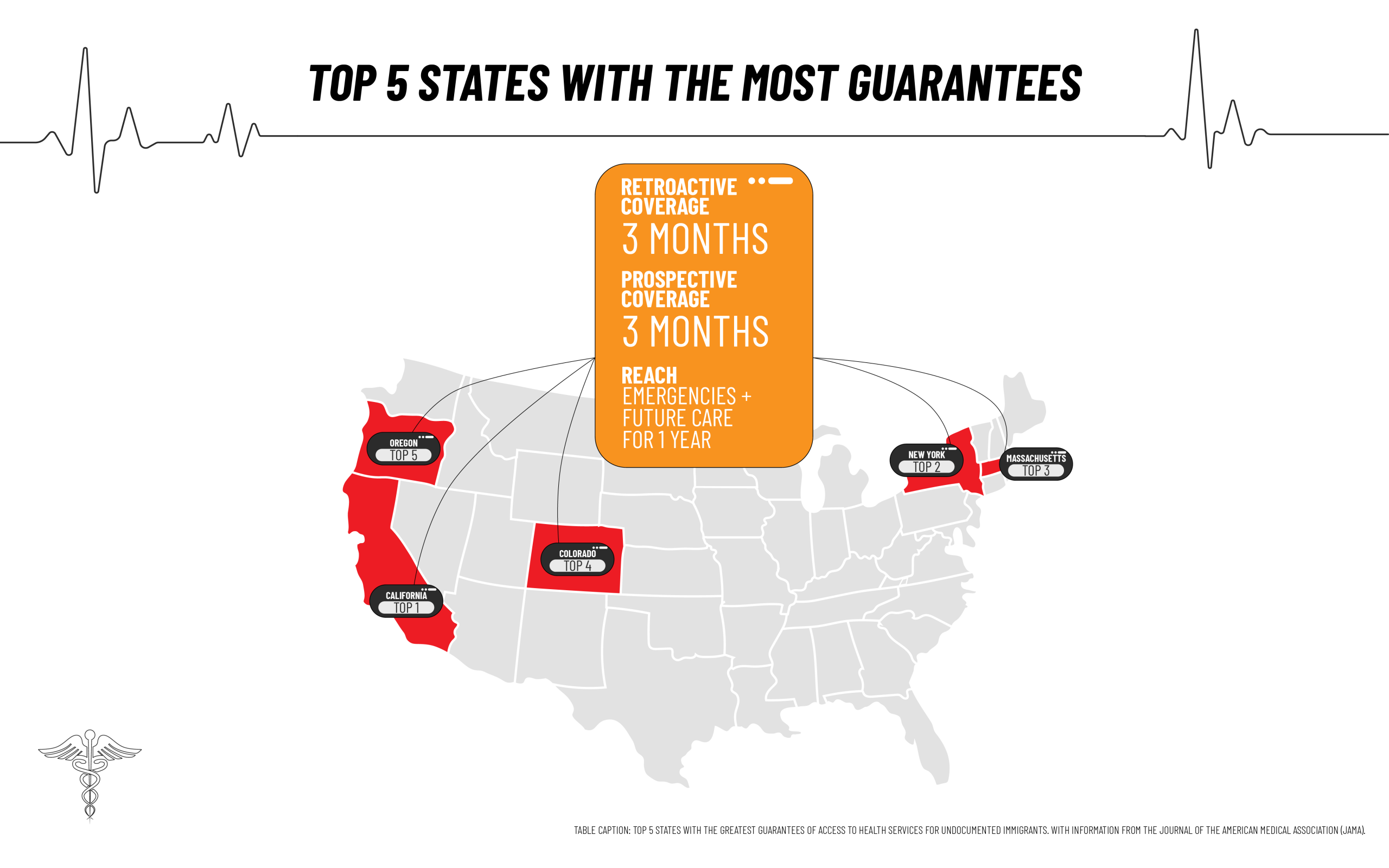

The states that provide the most guarantees in health care to migrants

Five states stand out as those that offer the most health guarantees to undocumented immigrants: California, Colorado, Massachusetts, New York, and Oregon, which are also sanctuary states, meaning they promote policies to protect immigrants.

They all have one thing in common: they combine retroactive coverage for three months, allowing for recognition of past medical expenses, with coverage for up to 12 months afterward, ensuring that the individual has access not only to immediate emergencies, but also to future medical care for a full year.

This means that immigrants in these states don’t rely solely on emergency care, but rather have a broader and more stable protection framework, making them national benchmarks in terms of health inclusion.

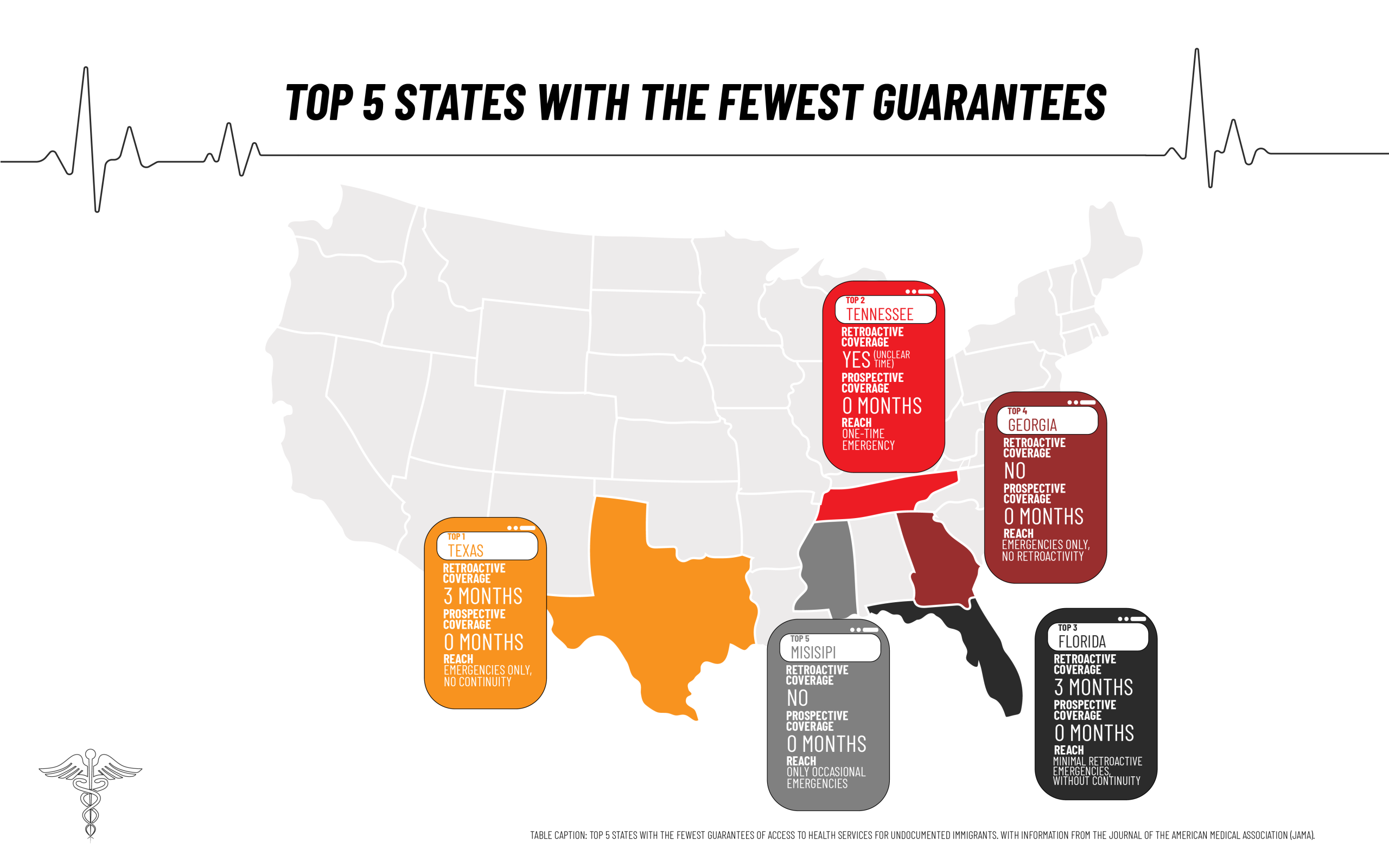

The states that provide the least health care guarantees to migrants

In contrast, the states that provide the fewest health care guarantees to undocumented immigrants are Texas, Tennessee, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi, states that are also not sanctuary states, meaning they do not promote policies to protect immigrants.

In these states, coverage is limited almost exclusively to emergency care, with no continuity of treatment or long-term access. Texas and Florida allow only three months of retroactive coverage but no prospective months, leaving migrants without protection once the emergency has passed.

Tennessee, for its part, provides emergency care, although with no clarity on the time covered, while Georgia and Mississippi don’t even include retroactivity. These policies reflect a restrictive and minimal approach; in these states, migrants can only receive assistance when their lives are in immediate danger.

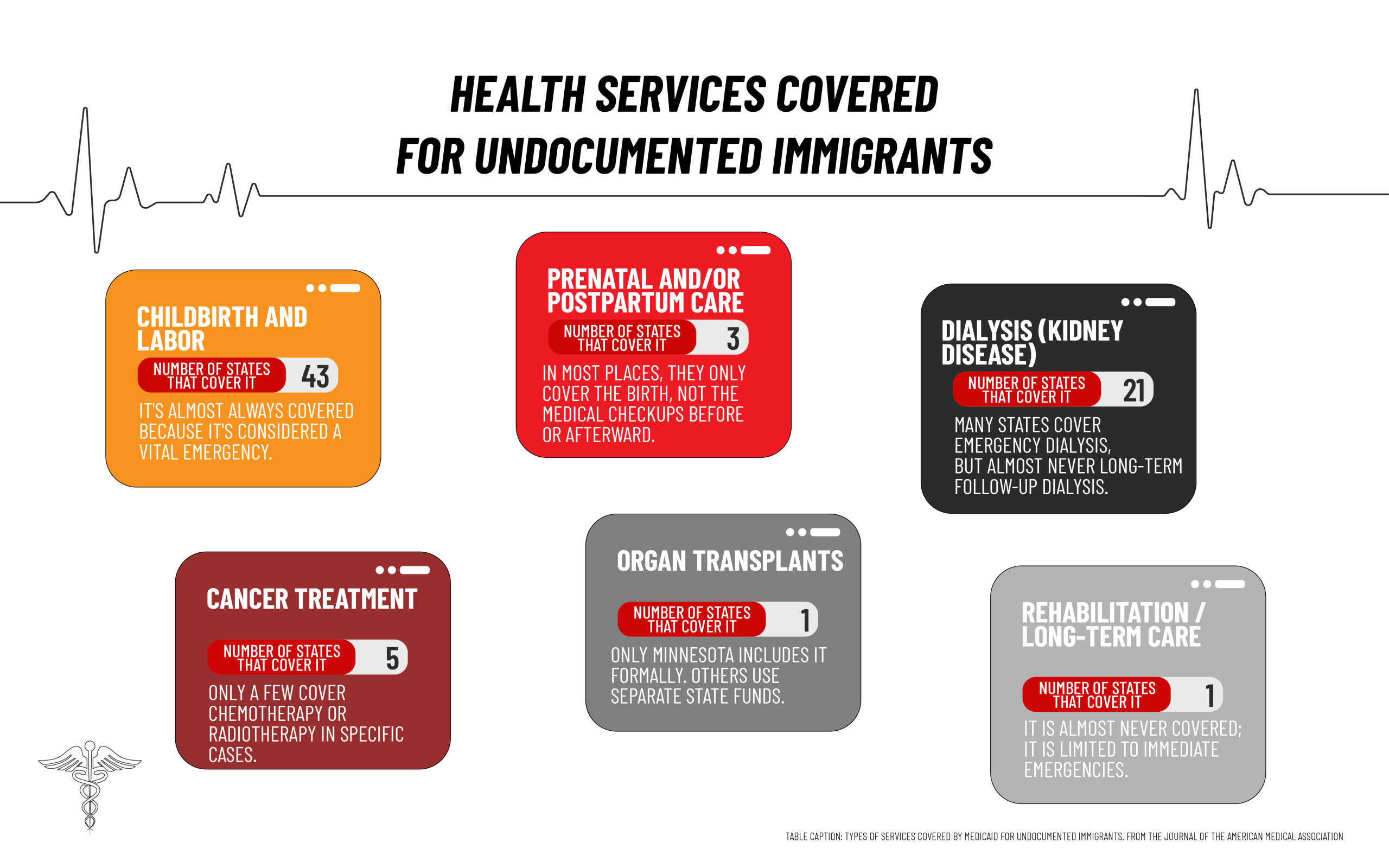

What services are covered by Medicaid for undocumented immigrants?

Emergency Medicaid coverage for immigrants in the United States focuses almost exclusively on critical and short-term cases, leaving out most ongoing or specialized health services. According to JAMA, coverage is divided as follows:

- Childbirth and labor are the most well-covered services: 84% of states include them and almost none exclude them.

- Prenatal and postpartum care is minimal, barely guaranteed in 6% of states.

- Organ transplants are virtually non-existent, offered only in Minnesota (2%).

- Dialysis is available in 41% of states, although it is almost always limited to emergencies.

- Cancer treatment is available in only 10% of states and is generally not comprehensive.

- Long-term care (rehabilitation and skilled nursing) is denied in 67% of states.

What is the coverage for legally resident migrants?

In several U.S. states, legal permanent residents, those who already have green cards, have access to certain health benefits, especially for children and pregnant women, although the rules vary widely.

For example, states like California, Colorado, Kentucky, New Jersey, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., offer both Medicaid and CHIP coverage for children and pregnant women, demonstrating a more inclusive approach. In contrast, in Florida, Louisiana, Texas, and Montana, coverage is limited to children only, excluding pregnant women.

Other states, such as Wyoming, restrict coverage only to pregnant women. This makes access to healthcare for immigrants in the United States highly unequal: in some states, children and pregnant women are covered, but in others, there are hardly any benefits. Everything depends on where you live, creating a highly fragmented and disparate landscape.

It should be noted that the general rule is that legal residents must wait five years after obtaining their green card to access Medicaid. However, in many states, children and pregnant women with regular immigration status can access the program immediately.

From citizens to undocumented immigrants, the disparities are evident.

2025, a new blow to undocumented immigrants’ access to health care

In July 2025, the Trump administration expanded restrictions on so-called federal public benefits for undocumented immigrants, implying a setback in access to health care and social programs. According to the new regulations from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), approximately 44 programs Previously considered exceptions, they are now included in the category of federal benefits prohibited for undocumented immigrants.

This directly affects initiatives such as community health clinics, family planning programs, mental health services and addiction treatment, which had functioned for years as gateways to address critical needs.

Furthermore, health-related educational programs, such as Head Start, which guarantee early intervention and medical checkups for children from low-income families, could also be out of reach for undocumented minors.

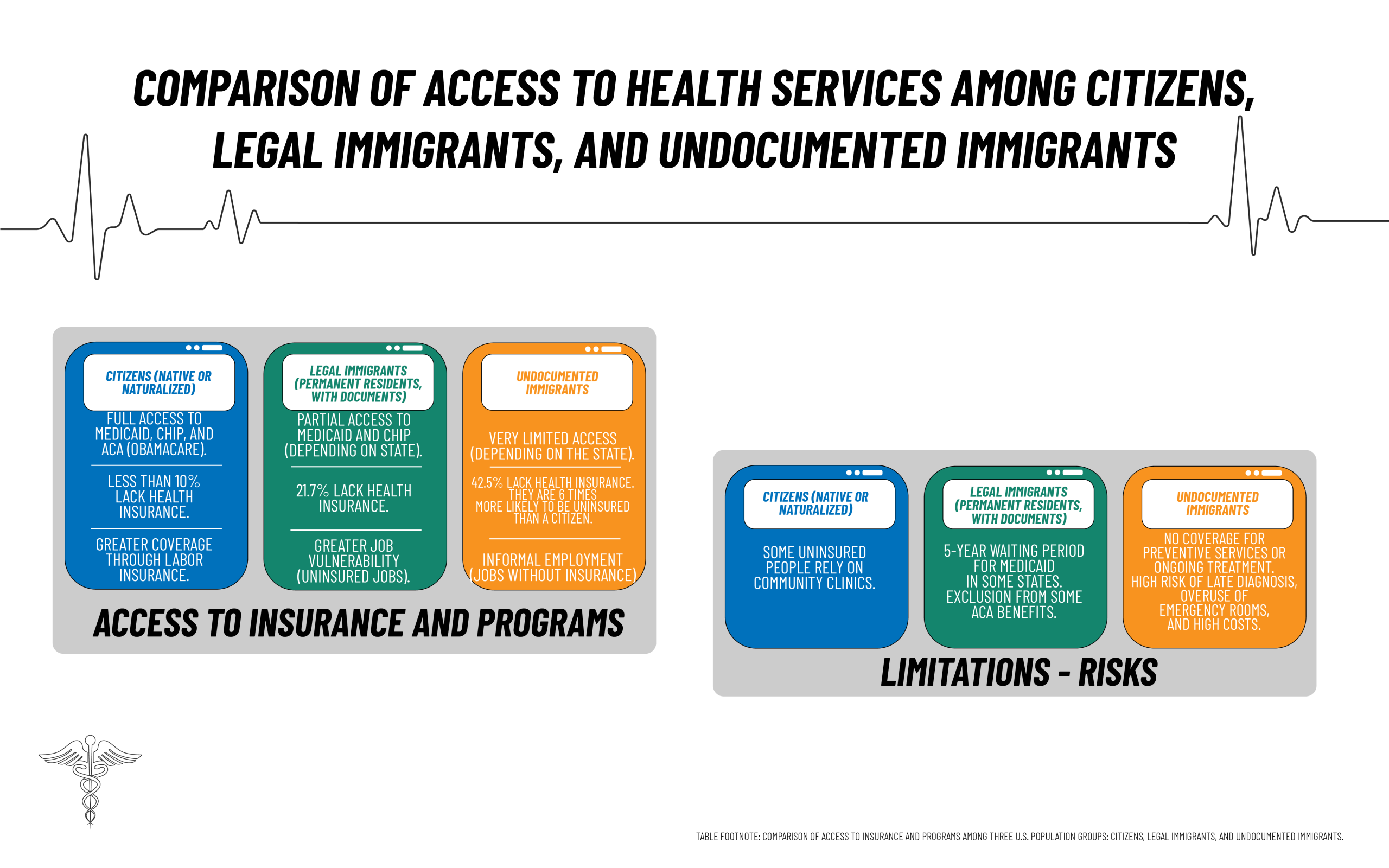

In conclusion, immigration status determines access to health insurance and health programs in the United States, generating what could be called a hierarchy of health rights.

At the top are citizens (native or naturalized), who have full access to Medicaid, CHIP, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA, known as Obamacare). Less than 10% are uninsured, and most are covered by employer-sponsored insurance. Those who are excluded rely primarily on community clinics.

immigrants (documented permanent residents) face an intermediate situation. While some states include children and pregnant women in programs like Medicaid and CHIP, a five-year waiting period persists. to access Medicaid in several locations, as well as partial exclusion from ACA benefits. As a result, 21.7% of this population lacks health insurance, and their access to job-related coverage is more limited due to their concentration in precarious jobs.

At the most vulnerable end of the spectrum are undocumented immigrants. Their access is restricted almost exclusively to emergencies covered by Medicaid, such as urgent childbirth or surgery, and in some states, it is minimally expanded through state programs. However, in the most restrictive states, only immediate emergencies are treated.

42.5 % of the population is uninsured, meaning they are six times more likely to lack coverage than a citizen. This exclusion translates into a lack of preventive services and ongoing treatment, which increases late diagnoses, overuse of emergency rooms, and, consequently, healthcare costs.